Formulation of policy often fails to realize the intended outcome due to implementational challenges. Effective implementation of policies require a strong feedback mechanism. This article looks into Bangladesh’s governance reforms aimed at facilitating feedback mechanism.

A recent study conducted by the Brac Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD) highlights the effectiveness of Bangladesh’s various government grievance redressal services during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research shows how the progress made during the pandemic laid the foundations of a feedback state that consistently listens and responds to its citizens. This article looks into Bangladesh’s various governance reforms and initiatives to facilitate a responsive government for all its citizens.

In the context of developing nations like Bangladesh, there is a huge discrepancy between intention and implementation. Most well-thought out policies with all the good intentions in the world often just remain in government documents without actually benefiting the citizen groups for whom the policies were formulated in the first place. Lack of accountability and transparency and absence of a citizen-centric, participatory governance mechanism driven by bottom-up approach plague both policy formulation and implementation in countries like Bangladesh.

Do we always need wholesale, large reforms?

In fighting corruption or even implementing policies at the local level, we often wait and push for wholesale, large reforms in the governance and democratic process. Even though such massive reforms are pivotal and essential, we do not always need them as a tool to make our governance system more citizen friendly. Baby steps and small reforms, even from local levels, can eventually accumulate to materialize greater impacts for the people.

While pushing for large reforms may be lucrative, it is often difficult to actually translate such objectives into reality. Because when you are trying to uproot and fundamentally change the existing fashions and styles practiced by existing institutions, you have to face the resistance of a system that has been there for decades. Thus, while initiative to eventuate wide-ranging and all-inclusive reforms should be put in motion, reforms at a small scale should also be prioritized simultaneously.

Next question arises whether such baby steps are actually effective. An example can be drawn from Uganda, a country characterized by high levels of corruption often with the involvement of public officials.

The central government of Uganda provides student grants for each student to schools in order to maintain school buildings, purchase textbooks, and finance any additional programs that may be helpful for the students. When Ritva Reinikka and Jakob Svensson set out to find how much of these government funds are going to the schools, they found out only 13% of these funds reached these schools. More than half of the schools received nothing from these funds. These money that never went to the schools are perhaps being skimmed off by the local public officials.

The scene turned around when Reinikka and Svensson published their findings. Uganda’s Ministry of Finance started providing monthly information about the district wise allocation of funds for the schools in some of the country’s main national newspapers. Nearly half of the headmasters of these schools that didn’t receive the exact allocated fund initiated a formal complaint to the authorities. As a consequence, most of the schools received the money.

This case sheds light on a pretty interesting aspect of governance. If beneficiaries or citizens have adequate information about the public services, have a feedback mechanism where they can express their grievances and eventually the feedbacks are reflected upon by the relevant authorities, reforms can be facilitated in governance from a small-scale and benefit citizens. Awareness of citizens, here, is extremely crucial because if citizens do not know where and how they have been wronged, they can’t complain about it or seek justice. Information asymmetry regarding both the services and feedback mechanisms have to be addressed so that citizens are well-aware about their rights. Like the case of Uganda, manifestations of accountability, transparency and citizen participation can be possible even without wholesale reforms through fixing larger institutions.

View from Below: Bottom-Up Approach

Governments across the globe more than often make the error of adopting a top-down design in policy making and governance that result in exclusion of the citizens. Local realities and citizen’s perspectives are often overlooked while formulating and implementing policies. Citizens are often missing from the entire public service delivery chain. One of the reasons agent banking and mobile financial services became successful in Bangladesh which eventually led to the successful implementation of Government to Person (G2P) payments of Government of Bangladesh (GoB) for social security programs was because a bottom-up approach was adopted.

Instead of brick and mortar arrangements of banking which excludes different segments of the population (a top-down approach), mom and pops shops of locals in the neighborhoods facilitated last mile delivery of financial services in Bangladesh. Thus, instead of a one-size-fits-all policy, taking a view from the bottom is instrumental while customizing and tailoring different policies.

States as Companies; Citizens as Customers!

However, even for small-scale reforms and a bottom-up approach, states whether it is the United States or Bangladesh have to transform the way they view themselves. In the public sector, citizens are considered as beneficiaries – often viewed as a burden to the state for whom the government has to dispose of its resources. Street level bureaucrats in Bangladesh are often characterized by their reluctance and corrupt mindset. In some instances, the lackluster and mundane government offices demotivate citizens to avail the government services in the first place.

reasons behind the failure of public offices in providing service

Monopoly over Government Services

First, public or government organizations have a monopoly over government services. Citizens are left with no other alternative except from knocking the doors of government offices as they can’t just switch to another alternative. If someone wants to purchase a mobile phone, they can choose from a wide range of options – from Apple to Samsung. But if someone wants to get a passport, there is only one entity that has such an offering – the state. One way to get what you want from the state is holding the government and political parties accountable through elections. If you hate the service delivery of one government, you can simply vote them out. However, even democracy often falls short when citizens are treated almost the same under successive governments formed by different political parties. Then, the only option people have is to leave the country and settle in a foreign land because the state has simply failed to gain the trust and confidence of its own citizens.

Lack of Incentive

Secondly, there is almost no pressure or incentive for the government service providers to improve their services or service delivery.

Information Asymmetry

And thirdly, information asymmetry restricts citizens to access services or provide feedback in the first place as they are not well-informed about their rights.

Thus, states, across the globe, not just Bangladesh, have to transform themselves with a new outlook where states will act as companies and citizens as customers – not beneficiaries. When the government performs as a giant company which has to make all its customers happy and satisfied with its services, then it will improve the citizen experience of each country – just like customer experience.

So how does a giant company perform? In simple terms, it segments and targets its market and develops products and services according to the targeted group. The government also needs to do the same. Different groups whether they are insolvent or disadvantaged require solutions and services that are tailor made for them. Then, it markets the product or service so that customers purchase it by making them aware about their existence. The government also should inform the public about its services so that people can extract the benefits. And finally, the company takes customer feedback and makes changes to its product or service and its delivery by reflecting upon the feedback. Thus, the government should have multiple mechanisms to take feedback from different groups and change and/or adapt its policies or services accordingly.

Governance Reforms & Initiatives of GoB

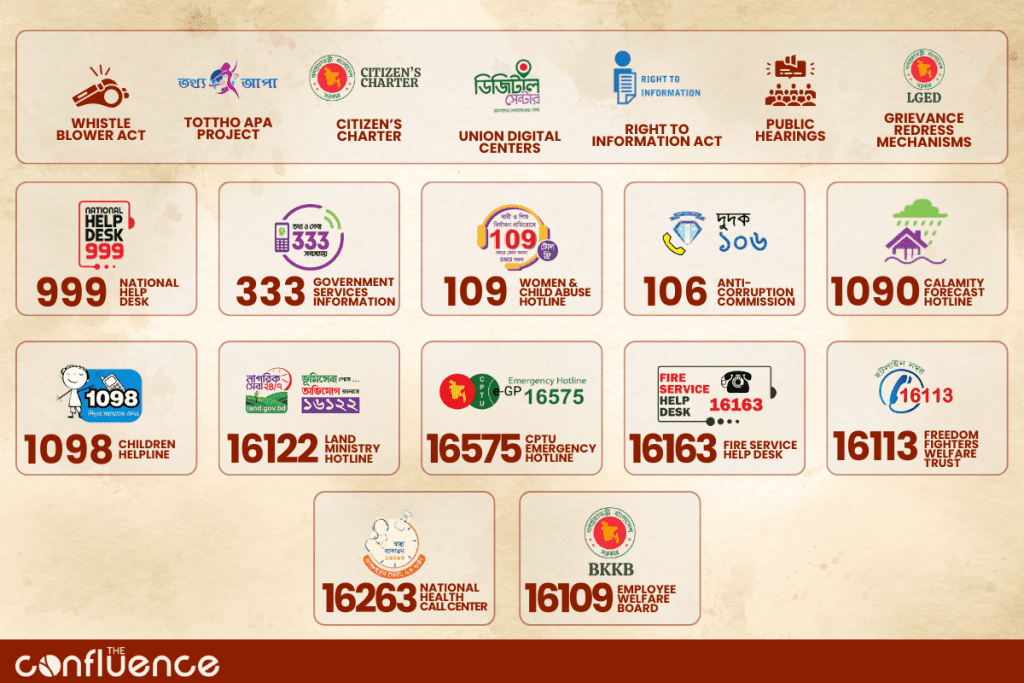

The Government of Bangladesh (GoB) has undertaken several governance reforms to make the development of the country more pro-citizen and participatory.

Following are some of the key governance reforms designed and/or implemented by the government:

Right to Information (RTI) Act 2009

In 2009, the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) enacted the Right to Information (RTI) Act. This act signifies the importance of citizens’ access to information to strengthen the country’s governance, and combating corruption. The act empowers the government offices to increase its responsiveness to citizens. According to the RTI, the Information Commission, Bangladesh was established as an independent statutory body to ensure free flow of information to the citizens.

The Section 4 of the RTI states that “Every citizen has a right to information from the Authority and the Authority shall on demand from a citizen be bound to provide information.” The importance of the RTI is it not only equips citizens with information but also provides the power and ability to act upon it. Because when people can gain information, they will have the capacity to make decisions and exercise their rights effectively.

Citizen’s Charter (CC)

In June 1991, the John Major’s government in the United Kingdom introduced the first ever Citizen’s Charter (CC). A citizen charter is basically a document that outlines all the details of the services and commitments delivered by different public offices, including the avenues for grievance redressal. The Citzen’s Charter was first introduced in various public offices by the Cabinet DIvision in 2007 which adopted a top-down approach. To take a more bottom-up approach and make CC participatory in nature, the Civil Service Change Management Program (CSCMP) of the Ministry of Public Administration launched the Second Generation Citizen’s Charter in 2010.

The RTI act strengthened the Citizens’ Charter Initiative as the CC is one of the major implementations of the act. The Citizen’s Charter in Bangladesh’s various public offices lists all the pertinent information regarding the quality, delivery, cost, time, contact point and complaint/feedback mechanism so that citizens can hold the public service providers accountable.

Both the RTI act and Citizen’s Charter have laid the foundation for building a feedback state in Bangladesh as they welcome dialogue and responses directly from the citizens. Citizens now are empowered to voice their demands, and grievances to the authorities which have laid the groundwork for various grievance redressal systems in Bangladesh.

Whistleblower Protection Act 2011

The government offices in Bangladesh have its colonial roots of corruption that remain persistent till this date. The public officials in these offices witness corrupt practices and opportunistic behavior of their colleagues every day. However, none of them can speak out against their colleague’s corruption or file complaints because they are not informed about a groundbreaking legislation that provides legal protection to government officials who will report the crimes of their co-workers. In 2011, Bangladesh Parliament enacted the Public Interest Information Disclosure (Provide Protection) Act, often referred to as Whistleblower Protection Act.

This act, alongside the RTI act, is instrumental in fighting corruption and holding government officials accountable. According to the Whistleblower Protection Act, “public interest information” means any information which discloses the involvement of officials in – irregular or unapproved expenditure of public money; mismanagement of public property; misappropriation or misuse of public property; abuse or maladministration of power; committing criminal offense or unlawful or illegal act; any activity harmful or threatening to public health, security or environment; corruption,

Any government officials can reveal and report the above mentioned public interest information to the pertinent authorities so that the public service delivery becomes transparent, corruption free and citizen friendly, However, whenever someone blows the whistle, it comes at the expense of their imminent loss of job or reputation and myriad of other threats. Thus, the act offers legal protection to the whistleblowers to motivate government officials to come in front. In the Section 5, Protection of Disclosure, the act states that the identity of the whistleblower will not be revealed to anyone without their consent. Also, no criminal or civil proceedings will be undertaken against the whistleblower for disclosing the information. Whistleblowers cannot be called as witnesses in the court after the information is disclosed. Any information provided by the whistleblower is not admissible as evidence in any civil or criminal case. If the whistleblower is a government employee, they won’t be subjected to demotion to any lower post or to harassment by transfer, or to compulsory retirement.

Tottho Apa Project

Bangladeshi women are the victim of thousands of years of deeply rooted patriarchy in which the societal forces hijacked their ability to assert themselves. In the past two decades, the country has made significant strides in women empowerment. To increase accessibility of women to information and technology, the Ministry of Women and Children Affairs of GoB has undertaken an innovative project, namely “Tottho Apa”. Educated young women are recruited to act as information providers or “Tottho Apa” who personally contact and outreach women at Upazila levels to provide them information, technology, and health services.

The project aims to establish 490 information centers at sub-national level across Bangladesh to provide all sorts of information services as well as E-Commerce support. The project has launched an e-commerce website, laalsobuj.com that aggregates products made by rural women entrepreneurs and sells those products through the website and mobile app.

Union Digital Centres (UDCs): Service Delivery Decentralized

In the past, the public services were largely inaccessible to citizens. Citizens had to travel long distances, spend on travel expenses and wait in long queues to avail the services. The Digital Bangladesh Campaign increased accessibility to internet and information technologies, including mobile phones.

On the foundations of Digital Bangladesh Initiative, on November 11, 2010, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina inaugurated Union Digital Centres in each of the 4,571 union or rural councils of Bangladesh with the aim of bridging the information gap and directly providing public services to citizens. Till November 2021, the GoB has established 8,280 digital centers across Bangladesh where around 15,000 entrepreneurs have already delivered 60.50 crore services. By digitalization of more than 300 services, the UDCs eliminated the Time, Cost, Number of Visits (TVC) from the public service delivery chain and put the citizens back into the equation through decentralizing public service delivery.

From the Graveyard of Old Complaint Boxes

In the past, though rarely seen, some public offices had a complaint box where people can write a complaint anonymously. The letters in the old complaint boxes only managed to gather dust remaining inside the boxes for years, instead of any real action from the authorities. It’s not enough to make people aware about their rights and public services. If public service providers fail to ensure the services to citizens, like any company, the state must have a feedback mechanism. It is a priority to transform Bangladesh into a feedback state where citizens will be treated as customers and they can file complaints and express their grievances without any harassment.

Public Hearings

At the local or community level in Bangladesh, people gather in a place to convery and raise their concerns, pain points and complaints to the government officials and public service providers. To ensure accountability, transparency and pro-citizen governance, Bangladesh’s Anti Corruption Commission (ACC) organizes public hearings at the Upazila Level. The public hearings facilitate transparency to make information available, publicity to make information accessible, and accountability to act upon the information and hold the responsible agents liable.

These public hearings at the local level address various governance and public service delivery issues such as land management issues, including land registration, settlement, and administration, health, rural electrification, and so on.

To institutionalize the public hearings at the Upazila Parishads (UPs), the Local Government Division (LGD), under the Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Co-Operatives of GoB has published guidelines in January 2022 with the assistance of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)’s Efficient and Accountable Local Governance (EALG) project. As per the guidelines, the public hearings will be organized fortnightly (every two weeks) at the UP level and once a year at the ward level. From 2019 to 2021, UNDP’s EALG project collaborating with the local government arranged 104 public hearing sessions.

Government Messaging and Broadcasting

During the pandemic, the government continuously disseminated information regarding COVID-19, and necessary health services, including vaccination through above-the line (ATL), below-the-line (BTL), and through-the-line (TTL) marketing. The government used loudspeaker (miking) announcements at the local level while campaigning through television channels, newspaper and social media platforms like Facebook.

Citizens accessed information from the government throughout the pandemic from various various channels. The BIGD research reveals that 70% of the respondents in the survey accessed information regarding COVID-19 from non-state television channels, and 34% got information from the state-owned channel, Bangladesh Television (BTV). 39% received information through social media and telephone-based messaging (either from mobile phone operators or direct government SMS). And 37% gained information from local governmental representatives or through loudspeaker announcements in their neighborhood.

Shastho Batayon Telephone Health Service

The GoB currently operates several hotlines and helplines to provide information, public services and take feedback directly from the citizens. One of them is the national health call center, Shastho Batayon (16263) that not only provides health related information 24/7 but also collects grievances and recommendations directly from the citizens to improve its service delivery. Shashtho Batayon received around 11 million and 3 million calls in 2020 and 2021, respectively. After collecting the complaints about service conditions from the users and beneficiaries, the complaints are fed into the Management Information System (MIS) of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) and the Directorate General Health Services (DGHS).

Helpline for Government Services Information (333)

Though the toll-free helpline number 333 was originally launched to provide government services information, the purpose of the helpline expanded, especially during the pandemic, when the helpline was used to gather complaints about public services offered by various government agencies and ministries. Since the launch of the helpline in 2018 by the a2i (Aspire to Innovate) unit of the Cabinet Division and ICT Division, the government helpdesk has received nearly 84 million calls on different governance and social issues, including social security services, child marriage, land-related issues and so on. The complaints aggregated through 333 are then collected by government agencies to feed into their own systems from grievance redressal.

Surokkha: Delivering Vaccine through Tech

The GoB digitalized the entire vaccine delivery chain by launching the national portal ‘Surokkha’ (www.surokkha.gov.bd) and subsequently a vaccination app of the same name. By leveraging Bangladesh’s past experience of rolling out mass immunization campaigns, the government with its strong priority to contain the pandemic, have led to the success of the COVID Vaccination Program. The Surokkha portal and app allowed the government to enroll and connect the citizens to the vaccination program. Citizens were able to register through Surokkha which allowed the government to effectively target citizens, decrease bureaucratic red tape and corruption while estimating the aggregate demand for vaccines in the country.

Grievance Redress System in the Health Sector

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) and the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) have developed an integrated system to manage feedback and complaints from citizens. This central grievance redress system (GRS) allows citizens to report their complaints and grievances anonymously. Feedbacks received through in-person interactions, online portals and other government helplines are also fed into the system. The transparent nature of the GRS allows it to display the complaints and feedback in the portal in real time, including the timing and location of the facility about which the feedback is being given.

During the pandemic, the GRS received feedback mostly on vaccine delivery. However, currently, citizens offer a myriad of complaints and concerns regarding different health sector issues in the system. The system is user-friendly and takes a system tracking approach which enables both the citizens and policymakers alike. Policymakers can now take actions by viewing the complaints both at the local or facility level and national policy level. At the facility level, some of the major complaints received by the GRS are lack of cleanliness of the health service provider facilities, inadequate supply of drugs etc., and at national level the single largest complaint is the inadequate number of staff in health care facilities.

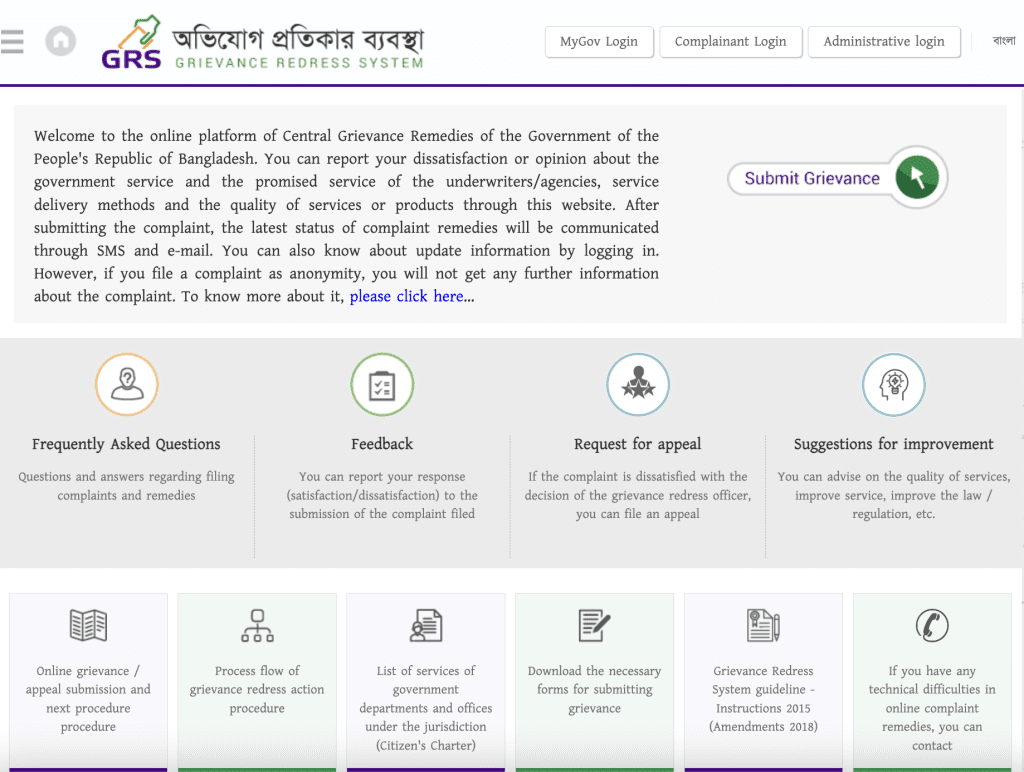

Central Grievance Redress System (GRS)

In 1986, the manual grievance redress system was first introduced in Bangladesh which significantly lacked user-friendliness. In 2015, the Aspire to Innovate (a2i) program launched the fully online and digitalized central GRS system (https://grs.gov.bd/) which is now monitored by the Cabinet Division and all the Ministries or Divisions of GoB.

Currently, 21 out of 64 districts have a fully functional online GRS system. Even though most public services are provided at the sub-district level, the coverage of the GRS system is only limited at the district level. The central GRS system empowers people to exercise their rights through directly filing complaints and getting redressal or solution after concerned authorities reflect upon the complaints. Since May 2020, the GRS system has been executed in over 8,000 government offices across Bangladesh and around 7,000 users have used the GRS to submit their grievances. A total of over 3,000 complaints were received through the GRS since May 2020 according to a study.

Recommendations

Increasing mass awareness regarding all legislations, initiatives and grievance redressal mechanisms should be prioritized by the government. When citizens will be well-informed about the scopes and limits to exercise their rights and the government reforms, then they will be empowered to participate in the governance of Bangladesh. Thus, citizen’s awareness is the antecedent of materializing all the efforts of GoB to address the principal-agent problem, corruption, poor public service quality, and decentralization of public services.

Strengthening the coverage and execution of the central grievance redressal system. Fragmentation of feedback mechanisms restricts concerned authorities to take swift action on the complaints. Such fragmentation creates hassle for both the policymakers and the citizens. Thus, the government should bring all the government offices, ministries and divisions under the same umbrella for facilitating a unified system for feedback and response while keeping dedicated grievance redressal systems for priority sectors like health.

At the same time, increasing the quality of interaction and service through frontline public officials or street level bureaucrats is also key to making Bangladesh a feedback state as so many citizens still put a premium on real life, face-to-face interactions.

About the Author

Shah Adaan Uzzaman is the Blog Administrator at The Confluence. A former Bangladesh Television Debate Champion and winner of several policy & debate competitions, he is currently a student of IBA, University of Dhaka.