Recently, there have been widespread social media campaigns for early marriage, specially of women and the ‘perceived’ needlessness of their education after a certain level from specific quarters of the society. We take a look at the female education scenario of Bangladesh, where did we begin, how far have we reached in the last 3 decades and how far we need to go.

Back in the days, women in Bangladesh had to struggle to achieve equal status to men due to societal norms that enforced restrictive gender roles as well as poor implementation of laws that were set to protect women. After the independence of Bangladesh, the government concentrated on expanding access to elementary education for all children, regardless of gender, and efforts were made to lay a solid basis for female education. Still there are many difficulties related to female education.

“I was in class six at that time. My parents suddenly told me that there was no need for me to go to school starting next year. I remember what they told me: ‘stay at home until you are of age to go and work at the [Readymade] Garments Factory. That would be better for us.’ But after availing the Female Stipend Program from GoB, I can now go to school. I know I have the potential. Now I can prove it to others.”

Barriers to Female Education

Child marriage is a heinous act that violates a person’s right to an education. Bangladesh continues to have South Asia’s highest rate of child marriage. According to statistics from the World Bank and International Center for Research on Women, 10–30% of parents indicated that their children dropped out of secondary school as a result of child marriage or pregnancy.

On the other hand, Girls may miss school for an extended period of time or never again due to gender-based violence. According to a report provided to the High Court by the Inspector General of Police (IGP), there were 41,695 rape incidents reported nationwide between 2016 and 2022. Gender based violence often occurs in schools, known as ‘School-related gender-based violence’ (SRGBV), which UNESCO defines as: ‘Acts or threats of sexual, physical or psychological violence occurring in and around schools, perpetrated as a result of gender norms and stereotypes, and enforced by unequal power dynamics, that can often lead to girls under-performing and/or dropping out of school altogether.’ The prominence of patriarchy and the dominant idea being preached by different quarters that women should stay home and take care of their children being an ‘ideal housewife’ leads to such outcomes to some extent.

UNICEF reports that as a result of the aforementioned difficulties, 10% of girls never enroll, 34% drop out, and 28% finish school but do not pass or have the essential skills to find employment or continue their education. However, only 28% of Bangladeshi females graduate from high school with respectable grades.

Further impediments to schooling include poverty, safety concerns, lack of school and superstitions linked to religious beliefs.

Inception of Female Stipend Program

In order to promote the enrollment and retention of females in secondary education, the Female Stipend Program (FSP) was established in Bangladesh in 1982. This initiative, piloted with only six locations, expanded further in 1997 with its vibrant success.

Back in the early 1990s, the gender gap was seemingly high in schooling, particularly in South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. This affected almost every age group, but was more prominent in secondary school compared with other education levels. With an objective to ensure equal education accessibility for boys and girls, the government of Bangladesh enacted compulsory primary education and a waiver of tuition fees for girls from classes six through eight.

Female Secondary Stipend and Assistance Program (FSSAP)

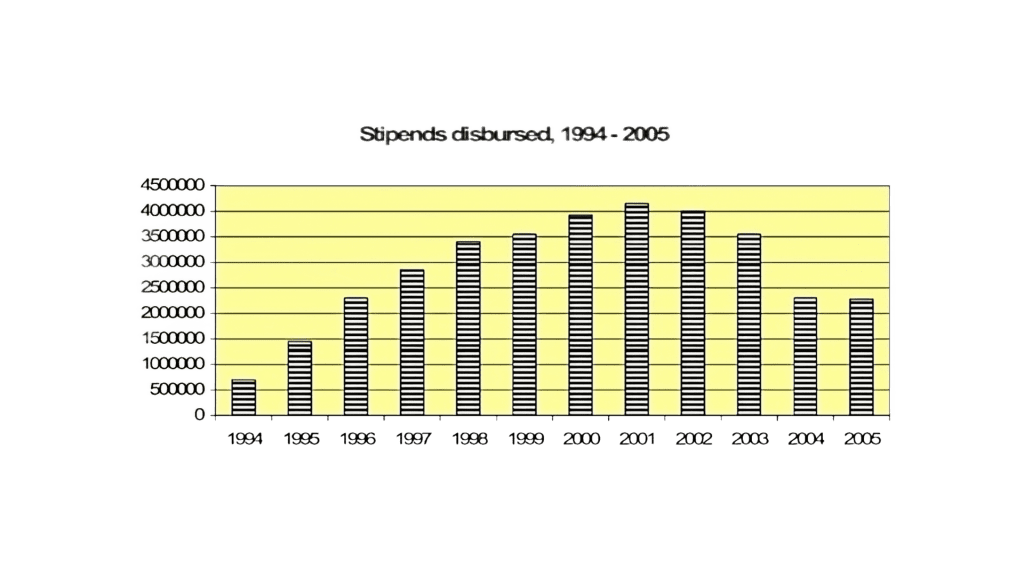

With the assistance of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), International Development Association (IDA) and other development partners, the government of Bangladesh launched the FSSAP in 1994 with the goals of promoting rural female secondary school enrollment and completion rates as well as discouraging early marriage. This program successfully enhanced the social, economic, and educational progress for women. The requirements included a minimum 75% attendance rate, a minimum 45% score on annual tests, and remaining single until taking the Secondary School Certificate (SSC) exam or becoming 18 years old. The three requirements have not changed over the FSP’s existence. All female students participating school who meet these requirements will be given a stipend amount that is specific to their grade level as well as other allowances that are immediately paid to their own bank accounts.

Breaking the Stigma around Female Education

Female participation in education has largely been hindered by the prevalent mentality that women are supposed to stay home, taking care of children and family members while the man in the family earns. When a girl receives scholarship money for going to school, financially insolvent families take it as an incentive. The specifically female-targeted incentives are still operational and have been scaled up later. Since the inception of stipends, women’s marital age has increased by a whole year proving its effectiveness against child marriage.

Number of Female Students in Secondary School

No Data Found

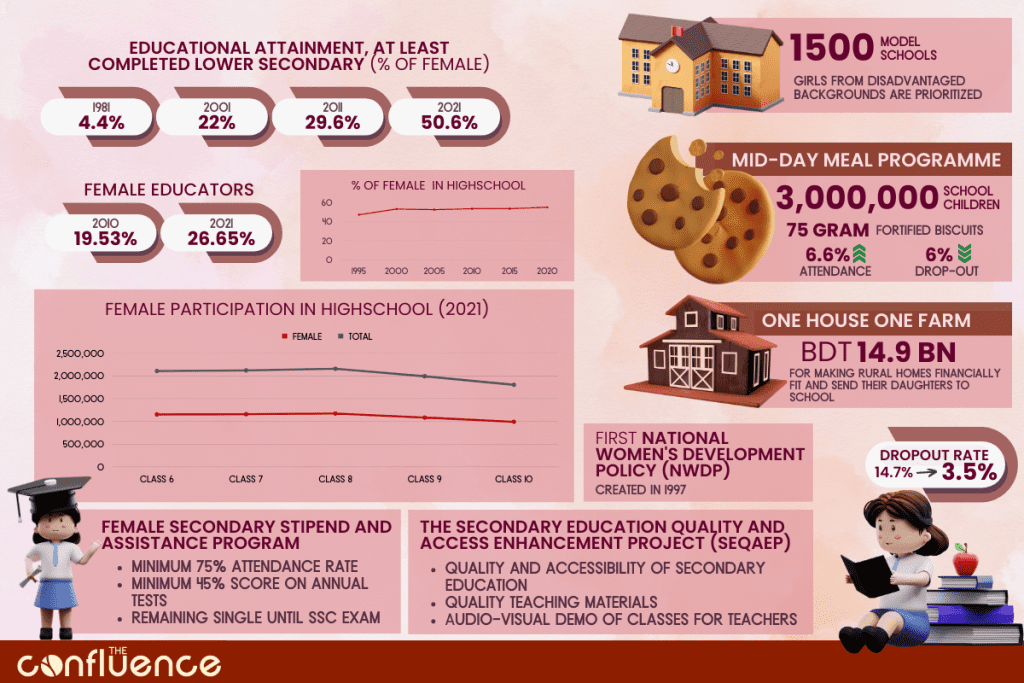

After considerable progress, the project was supported by a number of donors as well as the government through nationwide projects. The Human Rights Convention, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the Beijing Platform for Action, the Child Rights Convention, the Vienna Convention, and several ILO conventions are just a few of the agreements and conventions that Bangladesh has ratified. In response to the BPFA and the CEDAW, Bangladesh created its first national women’s development policy (NWDP) in 1997. The most recent update to the NWDP was completed in 2011. A National Action Plan was created in 2013 to implement the NWDP of 2011 and is now being modified to coincide with the SDGs.

Educational Transfers

The Food for Education Program and the Primary Education Stipend (Cash for Education) program are known as Educational Transfers. In 2002–2003, Food for Education was converted into Cash for Education. The Food for Education program, which was carried out in economically underprivileged rural unions, provided 15 kilograms of wheat or 12 kilograms of rice per month for one child attending school. Cash for Education enabled Tk 100 per month for one child and Tk 125 per month for more than one child.

Meal Programme to Support Education

The government also introduced a Mid-Day Meal Programme in 2010. Under that programme, the government provided 75 grams of fortified biscuits to around 3 million schoolchildren in 104 upazilas. According to the primary education ministry officials, the project saw attendance rise by 6.6 percent and dropouts fall by 6 percent in those schools. According to the Directorate of Primary Education, dropout rate at the primary level was 39.8 percent in 2010 and it fell to 14.15 percent in 2021.The GoB is planning to introduce a mid-day meal for students of all state-run primary schools starting from July 2023, in order to increase attendance and reduce dropouts. It aims to fulfill thirty percent of nutrition needs in students as well.

“When the school reopened after the COVID-19 period, I might not have been able to convince my family if I had not received this scholarship.

And if I didn’t get this scholarship, maybe I would have had to work to earn money. So I am very blessed and grateful to get this scholarship.”

Investment in the National Education Policy

An eight years long program, the National Education Policy was unveiled in 2010. It supports the requirement for gender equality in the classroom. In addition to encouraging female involvement and addressing social barriers that prevent girls from accessing school, the policy framework is primarily concerned with minimizing gender inequities.

The Secondary Education Quality and Access Enhancement Project (SEQAEP)

The SEQAEP project was launched by the GoB in 2011, aims to raise both the quality and accessibility of secondary education through quality teaching materials and audio-visual demo of classes to teachers and students and girls are also highlighted in this project.

The One House, One Farm Program

The program was established in 2009, with a budget of 14.9 billion taka. This initiative attempts to alleviate rural poverty by making farmers independent. This would improve the financial condition of people in rural areas and encourage parents to send their daughters to school by providing financial help to rural households for girls’ education.

Opening of Model Schools

The Ministry of Primary and Mass Education planned to open 1,500 model schools by 2020 to ensure cent percent education. The government has already established 1,324 primary schools by 2017 under the project in the areas where there is no school. Girls from disadvantaged backgrounds are prioritized for enrollment and retention in this program.

Role of Non-departmental Public Body

To encourage female participation in STEM fields, the British Council has launched the Women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) Scholarship Programme in 2021. The initiative aims at providing financial support to deserving female students who desire to pursue a career in STEM.

Where Do We Stand Now?

Women now have more access to possibilities for human growth. In this regard, the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) aim for gender parity in access to education at the primary and secondary levels was far exceeded. In both primary and secondary enrollment, girls outweigh boys.

Girls’ enrollment in secondary school increased by 7.7% by 2021 and dropout rates have decreased from 14.7% to 3.5%. Not only this, 50.95% of females could avail secondary education in 2021. The percentage of female educators also increased to 26.65% in 2021, whereas the rate was only 19.53% in 2010.

In 2018, the gender parity index in primary and secondary school was 1.10, up from 1.07 and 1.17 in 2017. The gender parity index for the tertiary education sector is now 0.70, up from 0.52 in 2005. The government is making every effort to lower the attrition rate of girls in secondary education in order to increase participation in tertiary education.

Bangladesh ranks 59th globally in terms of gender parity, with the highest gender parity in Southern Asia and a score of 72.2%. Bangladesh has a 93.6% parity in educational attainment. Over the past ten years, enrollment in secondary and tertiary education has gradually increased for both men and women. While enrollment in secondary school has reached full parity, there is still a persistent discrepancy between the literacy rate and enrollment in higher education. Bangladesh’s Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex performance ranks 139th globally with a parity of 43.8%. However, this represents a return to its parity level from 2020. Since 2021, the estimated earned income has improved, but the disparities in the other metrics have changed less.

Participation in Economic Activities – Still A Challenge to Overcome

As we notice, there seems to be a gradual improvement of the scenario. Female students used to drop-out from primary school once. Eventually we have achieved complete gender parity in high school – thanks to various efforts by the government, NGOs and development partners. However, gender parity is yet to be reached in higher education. In terms of economic participation of and opportunity women, Bangladesh ranks 139th globally. Hence the challenge still remains to bring half of the population into the workforce for further development of the country.

Even though female participation in important positions of the administrative service has increased significantly. Bangladesh Police, Army, Navy, Air Force are actively recruiting female members. They are working in the UN peacekeeping missions. Recently an All Female Formed Police Unit (FPU) has been sent to Haiti. The proportion of female police officers has increased five fold since 2008 according to Bangladesh Police Women Network. The percentage of female teachers in secondary schools increased from 20.28% in 2005 to 28.82% in 2021. In case of primary school, female teachers outnumber male teachers with 61.3% of the teachers being female. But these are mostly government facilitated employment opportunities for women.

Women participation in the informal economy is significantly higher. According to a2i’s report, 92% of women employment happens in the informal sector. However, women employed informally have a higher pay gap which is challenging to address. On the other hand, female participation in business is way lower. Only 4.5% of all businesses are owned by women. A tough country for women to be business owners. Other than businesses, female employees in the private sector still face significant challenges which need to be addressed. The UN Bangladesh Gender Parity Strategy 2023-2028 has already been taken and requires proper implementation in the future.

Suggested Reforms

To unleash the immense potential and promote the expansion of female education in Bangladesh, the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) can further intervene in the following way:

- Though the GoB provides scholarships to the female students, it is still not sufficient. By increasing the availability of Conditional Cash Transfer programs, immediate financial barriers can be reduced, motivating families to prioritize girls’ education. Moreover, this would result in higher enrollment and attendance rates among girls from low-income households as well.

- As people in rural areas feel unsafe about sending girls to school because of gender based violence. Wide-spread campaigning against eve-teasing and ensuring safety for female students is a must. The local government and administration need to play a crucial role in this regard.

- The school enrollment of girls has increased but still many female students drop out from the lack of transportation facilities. To address the transportation challenges and concerns faced by girls, GoB can introduce support schemes such as subsidizing transportation costs or establishing safe and well-founded transportation systems. These measures would facilitate easy access to schools for girls residing in remote areas.

- Gender-sensitive teaching methodologies can be introduced. These programs would foster a supportive and inclusive learning environment for females. Additionally, recruitment of more female teachers, particularly in areas where the presence of female instructors is limited can make the girls feel safe and increase the attendance rate.

- Educating parents and guardians about the massive significance of educating their daughters can bring a massive change. By arranging parental awareness programs, the government can address cultural and social norms that hinder girls’ education, while accentuating the long-term advantages that come with investing in their daughters’ education.

- The National Education Policy aimed at 1:30 teacher-student ratio by 2018. But the ratio was still 1:37 at primary level and 1:45 at secondary level. Thus, a thorough teacher recruitment and training program can help change the scenario.

About the Author

2 comments

[…] active participants in their communities, advocating for social change and addressing issues like gender-based violence and child marriage[2]. Their involvement fosters positive cultural transformation over time. It equips mothers with […]

[…] education refers to education of women. Female education in Bangladesh was not acceptable. In the past, there was a tradition among the people that women would live in […]