KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Pahela Boishakh has a long and rich history, with cultural and historical significance dating back to at least the Mughal era in the Bengal region.

- Mangal Shobhajatra, a traditional procession held during Pohela Boishakh, is not only a vibrant celebration of Bengali culture and heritage but also a powerful symbol of resistance against oppression and a reminder of the importance of unity and solidarity.

- The fact that Pahela Boishakh celebrations were targeted by dictators at different points in history and still continued to be celebrated despite attempts to suppress it highlights the resilience and importance of cultural traditions in the face of oppressive regimes.

- Measures should be taken to preserve and promote the indigenous cultural heritage associated with the New Year to ensure cultural diversity and inclusivity.

Almost all nation-states with rich political and cultural backgrounds have their own calendar. The only nation-state in the Bengal Delta region, Bangladesh, is not an exception to that.

Origin of the Bengali Calendar

Some might trace the origin of the Bengali almanac back to the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar, who ruled from 1556 to 1609. During this time, the economy of the region that is now Bangladesh was heavily reliant on agriculture. The tax collection system was based on the Hijri calendar, but the biodiversity and seasonal cycle were not aligned with it, causing a mismatch between the calendar and the natural cycle of the region. As a result, when it was time to collect taxes, farmers were often unable to pay because they were still waiting for their next harvest to come in. Some landlords resorted to physical force to collect taxes, which could lead to rebellion among the people. To avoid such situations, Akbar introduced a new calendar and the custom of celebrating the Bengali New Year. The festivities helped people forget their hardships and look forward to a better year ahead.

One might wonder, did this region have no calendar before the Mughals? Here it’s worth mentioning that the Bengali calendar is credited to Shashanka, a Bengali king who ruled during the seventh century. It is possible that a Bengali calendar predated Akbar’s reign because the term ‘Bangabda’ (Bangla year) is also found in two Shiva temples that are centuries older than Akbar’s time.

Fasholi Shan (The calendar of harvest), which we use today, was simply the result of Akbar’s request to the royal astronomer Fathullah Shirazi to combine the existing Hijri lunar calendar and the Indian solar calendar. Nawab Murshid Quli Khan, the Mughal governor of Bengal, may have been the first to use the ‘Punyaho’ custom as “a day for ceremonial land tax collection” and to launch the Bangla calendar using Akbar’s financial strategy.

According to Amartya Sen, Akbar’s official calendar, Tarikh-ilahi, was not used much outside of Akbar’s Mughal court, and after his death, the calendar he launched was abandoned. But there are traces of the “Tarikh-ilahi” that survive in the Bengali calendar.

The Bengali almanac was always a self-sustaining calendar. It took the names of the months from the names of the stars, and most of the names of the days came from various planets. The first month is called Boishakh, named after the Vishakha Nakshatra. Similar to other cultures, the first day of the year, known as Pahela Boishakh, is also celebrated in Bengali tradition.

The Traditional Celebration

Boishakhi Mela, a traditional rural fair, is one of the main cultural emblems of Bangladesh. The fairs would be conventionally set up under huge Banyan trees, where merchants from distant regions would convene to display their wares and playthings. Children could be found to enjoy nagardola(handmade swings); the potters would make Sokher Hari, an artistic pot, to sell at the fair. Just as Nabanna is associated with the eighth month of the Bengali calendar and is linked to farmers and their harvest, Haal Khata is a festival that is connected to the business community of Bengal. On the first day of Boishakh, namely Pahela Boishakh, traders close their previous ledgers and start new ones. Customers are encouraged to pay off previous debts and start over. In an effort to strengthen their relationship with customers, traders present them with treats, snacks, or gifts.

Controversy Concerning Religion: An Ignoble Attempt of Cultural Aggression

But it was only the reckless aggression of the Pakistani dictators that fueled the Bengali people to rekindle the New Year’s culture en masse. In 1967, Ayub Khan’s oppressive regime banned the poems of Rabindranath Tagore to suppress Bengali culture, but it instead sparked a quiet rebellion. The same year, the Chhayanaut movement protested this ban by observing New Year festivities at Ramna Park and singing Tagore’s songs, which became a powerful emblem of Bengali culture in East Pakistan. Following independence, this symbol became an integral part of Bangladesh’s nationalist movement and remains a cherished aspect of the country’s cultural heritage.

Prior to 1967, in 1966, a committee under the same regime led by Muhammad Shahidullah fixed Pahela Boishakhh on the 14th of April, which was not only a sign of colonial hangover but also unscientific. This mismatched adjustment was officially adopted in independent Bangladesh under the rule of another dictator, Hussain Muhammad Ershad, in 1987.

A Fightback on the Cultural Front

But the autocratic leader paid the price only in two years, when in 1989 the students of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Dhaka decided to demonstrate against the regime by arranging the Ananda Shobhajatra on Pahela Baishakh. The Ananda Shobhajatra is now known as the Mangal Shobhajtra. Today, this rally, Shobhajatra, became a distinctive tradition that takes place in every city in Bangladesh. Men can often be seen wearing red or white kurtas or photuas with traditional designs. Women and young girls, on the other hand, wear red and white saris with blouses and adorn flower crowns on their heads. It is believed that this color combination was inspired by the traditional ledgers used for Haal Khata, which had a red cover with white pages. Traditional ornaments and accessories are also worn to complement their outfits.

This rally is now regarded as a means of promoting unity and an expression of the Bangladeshi people’s secular identity. Each year the rally has a different theme related to the country’s culture, a particular issue, or political status. The procession in 2013 focused on the demand for the punishment of war criminals as its central theme, which caused significant dissatisfaction among radical Islamists and jihadists against the Mangal Shobhajatra.

But 2013 was not the first time when jihadists took a stance against the festival. In 2001, the New Year’s celebration of Chhayanaut came under a series of grenade attacks by the terrorist organization Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami. An editorial in The Daily Star stated, “This was an attack against the very identity of the nation; it was a blow against the very belief on which the War of Liberation was fought; it was a stab at the very ethos in which we take immense pride, both collectively and as individuals.” Although two cases were filed by the police on the same day, it took eight years to bring charges against Mufti Hannan and 13 others from the fundamentalist group due to a lack of government support from the BNP and Jammat-I-Islami regime. In 2014, eight of the accused were sentenced to death. However, the appeals related to the case have been pending with the High Court for nine years now. Additionally, a case under the Explosives Act in connection with the same incident is still under trial proceedings in a Dhaka court. Shishir Manir, a former general secretary of Islami Chhatra Shibir, an organization affiliated with Jammat-I-Islami and involved in the 1971 massacre of intellectuals, is now representing the militants in this case.

However, under the secular and central-left Hasina regime, in 2014, the Bangla Academy prepared a nomination file for the Mangal Shobhajatra festival, which was approved by the Ministry of Cultural Affairs of Bangladesh and submitted to UNESCO. On November 30, 2016, the festival was officially recognized as intangible cultural heritage by the Inter-governmental Committee on Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage of UNESCO at its 11th session. The following year, in 2017, West Bengal also adopted the festive Mangal Shobhajatra.

A Harmony of Ethnicities – Majority and Minority

Although the discussion so far might have given the impression that ‘Pahela Boishakh’ is exclusively a festival for the Bengali community, it is important to note that people from other ethnic minority groups in Bangladesh also celebrate their new year around the same time. Thus, the festival was hinted at as a celebration for the entire delta region at the start of the article.

Bizhu, Buisu, and Sangrai are the different names used for the New Year festival by the different ethnic groups of Bangladesh.

Buisu is a traditional New Year’s festival celebrated by the Tripuri people of Bangladesh. The name “Buisu” comes from the Tripuri word “bisi,” meaning “year.” It is one of the oldest and most significant festivals celebrated by the Tripuri people, bringing joy and enthusiasm to every household. The festival lasts for three days, beginning on the first day of the month of Vaishakh according to the Tripuri calendar. Although the exact dates may vary, the festival typically falls on April 12–14. Buisu is a social, cultural, and religious celebration that marks the start of the Tripuri New Year and is related to the solar New Year celebrations in South and Southeast Asia.

The Bangladeshi Marma and Rakhine ethnic groups celebrate their New Year, called Sangrai, from April 13 to 15 every year. It is one of the main traditional ceremonies of the Marmas, and the Rakhine also celebrate the New Year with their own traditions. The Marmas celebrate Sangrai for three days, including the last two days of the old year and the first day of the new year, according to the Marma calendar “Mraima Sakraoy”. Traditionally, these three days fell in the middle of April on the Gregorian calendar, but now they are observed on April 13, 14, and 15 in line with the Gregorian calendar. On the morning of the 13th, the traditional games of the Marmas are held with Pangchowai (Flower Sangrai), followed by the main Sangrai on the 14th, and the water on the 15th.

Bizhu, which is considered to be the most important socio-religious festival of the Chakma people, is also a Buddhist celebration. This festival is celebrated over three days, beginning one day prior to the last day of the month of Chaitra. The first day, known as Phool Bizu, involves decorating one’s home with an array of flowers. On the second day, Mhul Bizu commences with a bath in the river, followed by wearing new clothes and making rounds of the village. Women adorn themselves with pinon and hadi, while men wear silum and dudi. Special vegetable curries, such as “Paa Zawn Tawn,” homemade sweets, and traditional sports are enjoyed throughout the day. The day culminates with the Bizu dance.

The final day, Gawz che Pawz che dyin, involves the performance of various socio-religious activities. It is traditionally believed that the festival has an agricultural significance, as it takes place in mid-April, just after the first rain when zhum sowing begins. In the past, worship of the earth was conducted to ensure a prosperous harvest, which eventually evolved into the Bizu festival.

A Policy Issue – Holidays for Minority Festival

While it is a cause for celebration that the Bangladeshi government has provided holidays and bonuses for Pahela Boishakh, it is disheartening that there are no holidays granted for ethnic groups on their own cultural and religious festival days. Over the past few years, there has been an increasing call for holidays on these occasions. For instance, in 2022 and 2023, the Dhaka University Jum Literature and Cultural Society requested a holiday for their festivals.

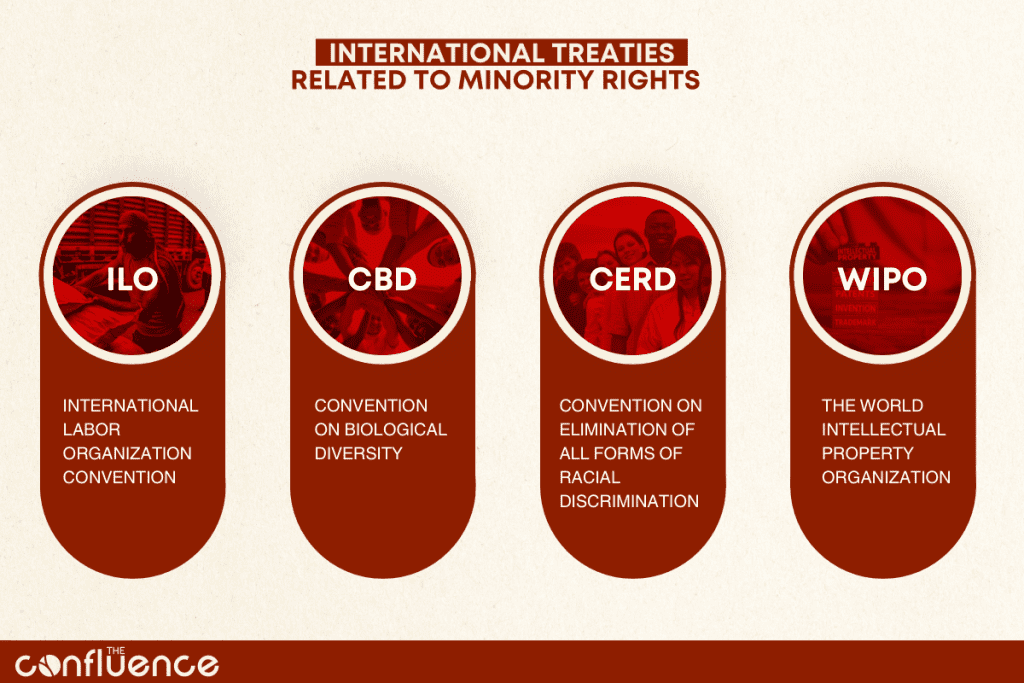

It is worth noting that the Bangladeshi government has entered into various international treaties that suggest the provision of holidays for minority ethnic groups.

Bangladesh is a signatory to various international treaties, including:

- International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention No. 169

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD)

- The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge, and Folklore

Although the International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention No. 169, also known as the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989, does not specifically address holiday rights, Article 8 of the convention recognizes the importance of indigenous peoples’ rights to maintain their distinct customs and institutions. This article emphasizes the need for governments to respect and protect indigenous peoples’ customary law, which could include the celebration of holidays and festivals. Therefore, the convention provides a framework for promoting and respecting the cultural rights of indigenous peoples, including their holiday traditions.

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) includes specific articles that recognize the importance of traditional knowledge and cultural practices of indigenous and local communities in the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity. Article 8(j) states that contracting parties should respect, preserve, and maintain the traditional knowledge, innovations, and practices of indigenous and local communities and promote their wider application while ensuring the equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization. These articles highlight the importance of involving indigenous and local communities in conservation and sustainable use efforts while respecting their cultural practices and traditional knowledge.

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) does not have a specific provision on the holiday rights of indigenous peoples. However, Article 5 recognizes the rights to equality before the law and the right to participate in cultural activities without discrimination, which are relevant to the protection and promotion of the holiday rights of indigenous peoples.

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) recognizes the importance of traditional knowledge and cultural expressions of indigenous peoples, which can include knowledge related to holidays or festival celebrations.

For example, the Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge, and Folklore (IGC) was established by WIPO to address intellectual property issues related to traditional knowledge, including those of indigenous peoples. The committee has recognized the importance of traditional knowledge and cultural expressions in the promotion and protection of indigenous peoples’ cultural heritage. Additionally, WIPO has provided technical assistance and capacity-building programs to help protect and promote traditional knowledge and cultural expressions, including those related to holiday or festival celebrations. These efforts aim to ensure that the intellectual property rights of indigenous peoples are respected and that their cultural heritage is preserved for future generations.

In addition to the international treaties, Article 23A of the Constitution of Bangladesh declares that the state shall take steps to protect and develop the unique local culture and traditions of the tribes, minor races, ethnic sects, and communities. This fundamental state principle imposes an obligation on the state to protect the unique local culture and traditions of various communities, even if the state is unable to fulfill its obligations due to unavoidable circumstances. At the very least, the state has to respect this principle, which means the state cannot take any deliberate action that goes against the principle. Therefore, the government cannot require individuals from ethnic sects to work on their cultural festival days. Hence, the government must issue holidays on these days.

A Policy Suggestion – Optional Holidays

But it is impractical for the government to provide a holiday for every festival, especially considering the minimum duration of 4 days required for such holidays. Nonetheless, the government could offer optional leave, which would allow individuals associated with a particular festival to take the day off.

The government provides three types of leave for its employees: general leave, executive-declared leave, and optional leave. The latter usually includes 7 to 9 days, with a maximum of 3 days off for each employee. In this regard, optional holidays can be granted to the Chakma, Tripura, and Marma communities on Biju, Baisu, and Sangrai, respectively. Meanwhile, educational institutions can consider adjusting their summer and/or winter vacation schedules to allow for a continuous break from April 12 to April 16. This would be a step towards preserving and promoting the indigenous cultural heritage associated with the New Year and ensuring cultural diversity and inclusivity.

Based on the discussion, it can be concluded that the Bengali New Year festival, Borsho Boron Utshob, is a secular and inclusive celebration that is not associated with any particular religion, community, or caste. Instead, the entire country of Bangladesh celebrates a festival that is deeply ingrained in its culture and heritage. Pahela Boishakh is a celebration of the soil and soul of the country. Thus, we all sing in unison to greet the New Year with the Tagore’s, “Eso He Boishakh Eso Eso.”

About the Author

Fahim Shihab Reywaj, a law student at the University of Dhaka, who expresses himself through debating, writing, and poems; a strong advocate of our national liberation struggle and aspires to achieve the fundamental aim declared in the preamble of our constitution. Often introduces himself by saying, ‘too human to be a seagull.’