This is the first part of a two-part article on media regulation in Bangladesh. In the first part, we look at the mainstream media landscape of the country, the need for regulation, and how the government has so far tackled, or attempted to tackle, the issue of regulation using the criminal justice system. In the second part, we will be looking at the Press Council of Bangladesh, and what role it can play in striking a balance between press freedom and responsible journalism, subject to appropriate reforms.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- After the independence of Bangladesh, for 25 years Bangladesh had no private media outlet which later emerged and till now this country has seen a boom of private media outlets.

- Due to immense competition within the media and independent content creators in social media space, click baits, misinformation, disinformation etc. also spread out.

- To stop online misinformation, Digital Security Act (DSA) was enacted which has scope of procedural abuse and journalists are disproportionately being a target of it.

Bangladesh Media Landscape

For the first 25 years of Bangladesh’s existence, there was only one television channel and one radio station, both owned and operated by the government. After Sheikh Hasina was elected as the Prime Minister in 1996, the media was opened to the private sector for the first time. Since then, the media landscape has flourished in Bangladesh. There are now 38 TV channels, and 26 radio stations, in operation. 701 newspapers are currently in print, of which 169 also have online versions. This is complimented by 170 standalone registered online news portals.

In recent years, and owing to the ‘Digital Bangladesh’ policy, the number of mobile and internet users have also grown exponentially. There are currently 125 million internet users and 182.6 million mobile users in Bangladesh. At the end of January 2023, the number of active Facebook users in the country stood at 46.5 million. This has resulted in a growth of citizens’ journalism, and for the first time in Bangladesh’s history, citizens (as in the general populace, who are not part of the civil society) are getting actively involved in political and policy discourses in the online space where the discourse is much more interactive and accessible in nature compared to previous modes of discourses.

Misinformation, Disinformation and Fake News

The proliferation of online based platforms in Bangladesh has resulted in severe competition among the news outlets for publishing the next ‘breaking story’. Additionally, monetization of citizens’ platforms like Facebook and YouTube has created a gold-rush among individual content creators. Thus, journalists are not only in competition with each other, but also with millions of individual content creators, for capturing the attention and imagination of readers and viewers. Unsurprisingly, the hyper-competitive media landscape has resulted in such phenomenon as click-bait headlines, sensationalization and “tabloidization of news, misinformation, disinformation, and even fake news.

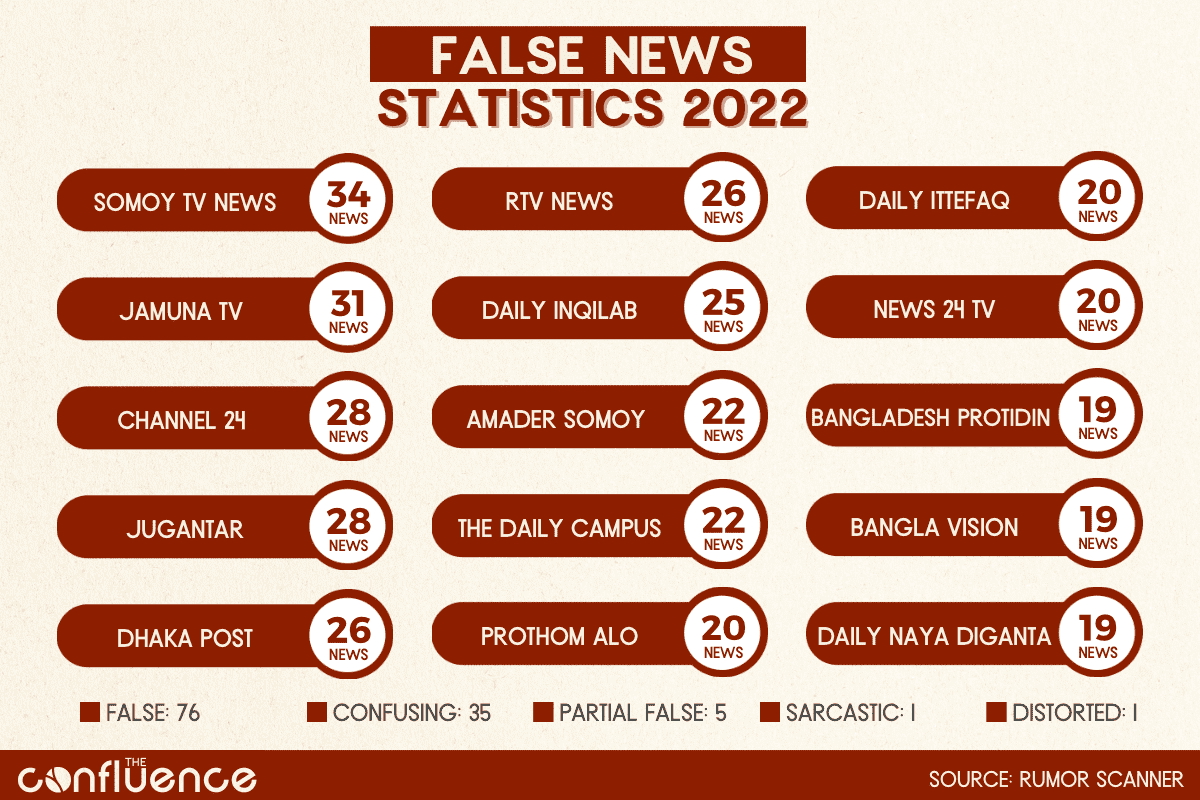

According to a recent research by the Global Disinformation Index (GDI), all 33 Bangladeshi news websites studied showed a medium to high risk of ‘disinforming’ their online users, including sites which are widely respected for their independent news coverage. This is consistent with the findings of independent fact-checking organizations. Boom BD, a third-party fact-checking partner of Facebook in Bangladesh, found 23 pieces of false or misleading news in top mainstream media between March and December 2020. In 2021, the same organization found at least 11 fake news in mainstream media. Another independent fact checker, Rumor Scanner, flagged a total of 1021 inaccuracies in 118 different incidents, published in 101 news media of the country throughout the year 2022. Even top-rated newspapers and channels such as Somoy TV, Prothom Alo, Kaler Kantho, and RTV featured in the top-ten of the list.

Sometimes the subject matter of such misleading or false news can be sensitive, like religion, thereby endangering lives and property. For example, on June 19, 2022, Dr. A F M Khalid Hossain’s article published in the ‘Daily Naya Diganta’ alleged that the new curriculum had repelled religious subjects, which was subsequently flagged as ‘false’ by the fact-checkers Rumor Scanner. Another recent story highlights the relative ease with which false or misleading news can be pushed in mainstream media. A teenager was able to create a fake website resembling that of the White House, and through high quality forgery, was able to deceive several mainstream media outlets, such as the Prothom Alo, into publishing a false news of his winning a prestigious but non-existent debate competition!

Sometimes the subject matter of such misleading or false news can be sensitive, like religion, thereby endangering lives and property. For example, on June 19, 2022, Dr. A F M Khalid Hossain’s article published in the ‘Daily Naya Diganta’ alleged that the new curriculum had repelled religious subjects, which was subsequently flagged as ‘false’ by the fact-checkers Rumor Scanner. Another recent story highlights the relative ease with which false or misleading news can be pushed in mainstream media. A teenager was able to create a fake website resembling that of the White House, and through high quality forgery, was able to deceive several mainstream media outlets, such as the Prothom Alo, into publishing a false news of his winning a prestigious but non-existent debate competition!

Failure of Self-Regulation

It can be said that self-regulation in the media has also failed. One of the most notable examples of such failure is the fact that Mahfuz Anam, the editor of the Daily Star, has continued in his editorial role even after admitting on live TV that he published stories against top politicians of the country fed by the military intelligence agency, DGFI, during the military-backed caretaker government, without any verification whatsoever. By the same token, the editor of Prothom Alo, Motiur Rahman, wrote an editorial on June 11, 2007, asking that both leaders of the two major political parties, Awami League and the BNP, should retire from politics, at a time when the military was implementing a de-politicization campaign in Bangladesh by indiscriminately arresting politicians on trumped-up charges. By lending their influential voices to the infamous “minus two” formula, both the editors acted as enablers of the generals heading the extra-constitutional regime. In an ideal world, where self-regulation was a reality, both the editors would have resigned having apologized for their roles. But that did not happen, and they continue to edit both the newspapers to date.

Another glaring example of the lack of self-regulation in media came in the form of a deliberate fake news published by the (now defunct) Amar Desh newspaper. In 2013, Bangladesh was experiencing regular and violent agitation from the Jamaat-E-Islami, protesting the trial of their leaders for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the 1971 Liberation War. It was in this context that Amar Desh published a photo of the changing of Gilaf (cover) of Holy Kaa’ba with the caption that the image showed a human chain by top Islamic scholars to protest the war crimes trial in Bangladesh. For six months, Amar Desh did not issue any correction or apology. Suffice it to say the news in question was then widely circulated in social media to kindle communal tension and greatly contributed to the wholesale violence which ensued.

Use of the Digital Security Act

In the absence of effective self-regulation in the media, the government had to step in and introduce laws in this regard. This includes the controversial Digital Security Act (DSA), 2018, and its predecessor, the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Act, 2006 (as amended in 2013). The DSA is particular has been an issue of concern for journalists for the following reasons:

First, the DSA was never meant to be a forum for regulating the mainstream media. The predecessor of the DSA, the ICT Act, came about as a response to several high profile incidents of fake news and rumours which resulted in breach of peace, communal tensions, sectarian violence, and public panic, in 2013, including, among others: the attack on Buddhists in Ramu, violence against Hindus following the conviction of Jamaat-E-Islami leader Delwar Hossain Sayeedee using a photo-shopped image, and the rumour regarding Vitamin-A campaign by the Jamaat-run page Basherkella. The DSA too (at least the relevant sections), was enacted for the same purpose of tackling the challenge of fake news and online rumours. The lawmakers intended the Act to be a weapon against such incidents as, the rumour regarding Padma Bridge and human child sacrifices, instigating communal violence online, and spreading misinformation about vaccines during the pandemic.

Second, the criminal nature of the offenses under DSA, including for defamation, makes it particularly harsh for journalists. Whether under the DSA, or the conventional Penal Code, defamation in Bangladesh is tried as a criminal matter, with the main relief for an aggrieved person being the imprisonment of the defamer. It should be noted that decriminalization of defamation laws, and transfer of defamation exclusively to the civil jurisdiction, has become an area of growing academic and professional interest which requires policy intervention.

Third, among the different professions of people slapped with DSA charges, journalists constitute the second largest group, a disproportionate number. Between January 2019 and August 2022, out of 1,029 accused charged under the DSA, 280 or 28% accused were journalists.

Fourth, some relevant sections of the DSA are not only arrestable but also non-bailable. Among the 280 journalists charged between January 2019 and August 2022, 84 were arrested. Given the nature of the offenses in the DSA, in general, there has been a lot of arrests. Since its enactment on October 8, 2018 until June 30, 2021, 2,607 arrests took place in 2,646 cases with 5,851 accused.

Fifth, the law is open to procedural abuse. Anyone can file a case under DSA against a journalist, even if he/she is not personally aggrieved in the matter. Even multiple cases can be filed against same accused from different jurisdictions. Usually, the case is filed against a journalist individually, and not against the newspaper or media itself.

Naturally, the use of DSA, in its current form, against journalists have given rise to concerns about press freedom and free speech. Association of journalists, human rights organizations, and even UN bodies have asked for amendment, even repeal, of the DSA. It is clear that the DSA is not an appropriate tool for media regulation. It is unnecessarily harsh, irrespective of the magnitude of the wrong involved, and very much open to procedural abuse. There is also no evidence to suggest that the use of DSA has resulted in more responsible behavior from the media.

Is there an alternative to the DSA which promotes both press freedom and responsible journalism at the same time? Experts and stakeholders have, for long, advocated for utilizing the Press Council of Bangladesh in this regard. We will examine the PCB as a suitable forum for media regulation in the second part of this series.

About the Author

Shah Ali Farhad is the founder and publisher of the Confluence. He is a lawyer, policy-researcher, and political activist. He is currently engaged with the Dhaka-based think-tank, the Centre for Research and Information (CRI), as its Senior Associate. He is an advocate of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh and a Barrister of the Lincoln’s Inn, UK. He previously served as a Special Assistant to the Prime Minister of Bangladesh. He holds a masters of public policy (MPP) from the University of Oxford, and a masters in human rights law (LLM) from the University of Hong Kong.

1 comment

[…] will serve as a strong deterrent against yellow journalism. Additionally, as was stated in Part 1 of this article, defamation and libel allegations against journalists need to be treated as civil […]