The inherent cruelty of inflation lies in the disproportionate harm it levies on the poor. Robbing them of the true value of their incomes while eroding their savings, inflation can trigger intense discontent and unrest within a nation’s populace.

But containing inflation is no easy task, as the contributing forces can sometimes lie beyond a government or central bank’s control. Furthermore, the efficacy of retaliatory monetary policy by a central bank to combat inflation while ensuring growth depends on proper governance and accountability. It is no wonder then that the former Governor of the Federal Reserve, Ben S Bernanke, termed the fight against inflation the “bane of central bankers” since World War II.

Since May 2022, Bangladesh has experienced a steady surge in prices, particularly in food and fuel. Inflation in February clocked in at 8.78% after surpassing 9% in August and September last year.

The impact this has had on the nation’s poor must be appreciated in its entirety. Of the 1600 individuals from lower income groups (average monthly salary < Tk 14,000) polled by the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling:

- 19% went hungry for an entire day, compared to 9.75% last year

- 38% skipped meals, compared to 17.94% last year

- 72% said they ate less than they needed, compared to 42% last year

- 26% were at risk of severe hunger, compared to 12% last year

- 96% lowered meat consumption, 88% lowered fish consumption, 77% lowered egg consumption

- Average incomes stayed the same, whereas average expenses went up 13%

- 35% depleted their savings to meet expenses

- 74% borrowed funds to sustain their standard of living

The findings paint a tragic picture, one that lends credence to inflation’s notoriety as the cruelest tax on the poor.

Why is it so?

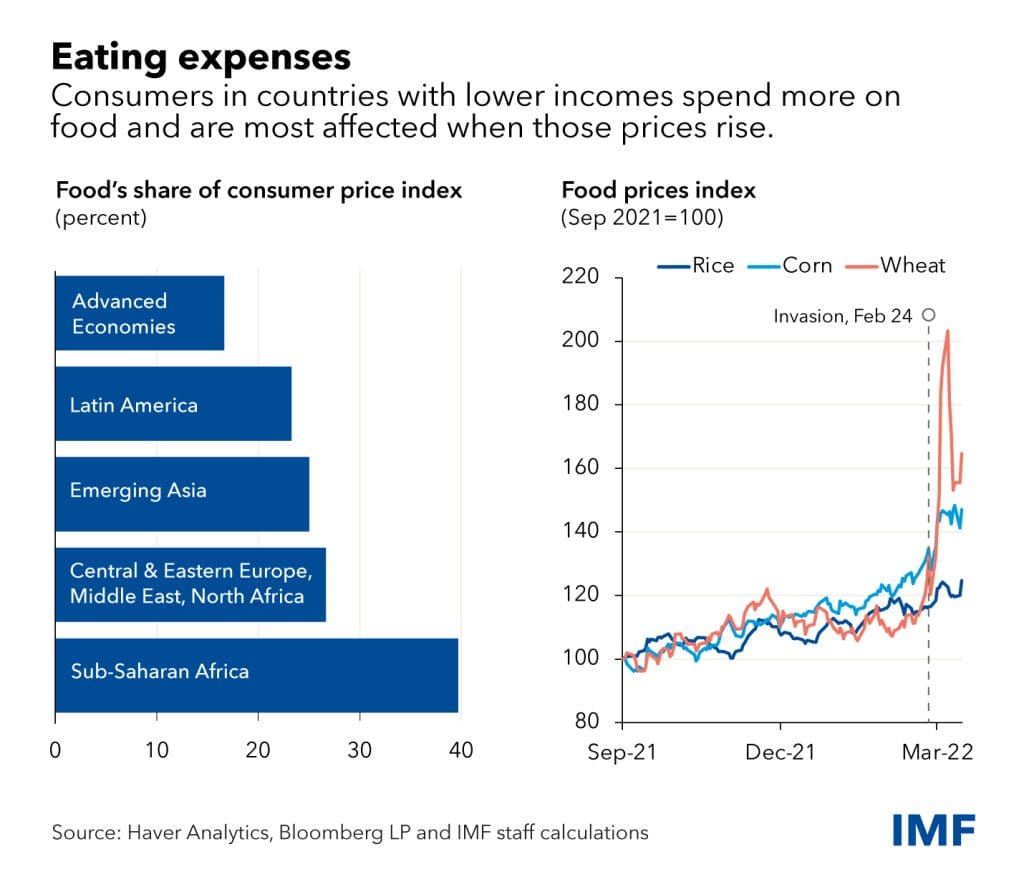

Since people from different income levels spend their income on different baskets of goods, the effects of inflation are not the same for everyone. Low to middle income families in developing countries such as Bangladesh spend an average of 60% of their income on food and, as such, are disproportionately hurt when food prices skyrocket. Moreover, the majority of incomes in Bangladesh – wages and transfer payments – are not designed to protect purchasing power and consequently remain vulnerable during inflationary periods. The rich enjoy investment and self-employment income, which are more likely to keep pace with rising prices.

If one considers how high-income households have greater levels of savings and safeguards during times of need, thanks to better access to financial products, it is easy to see why inflation is worsening inequality in Bangladesh.

Who to blame?

To evaluate the measures taken by Bangladesh Bank to curb the ongoing crisis and predict their efficacy, it is imperative to understand what is causing this persistent rise in prices. Different causes require different remedies and merit different expectations.

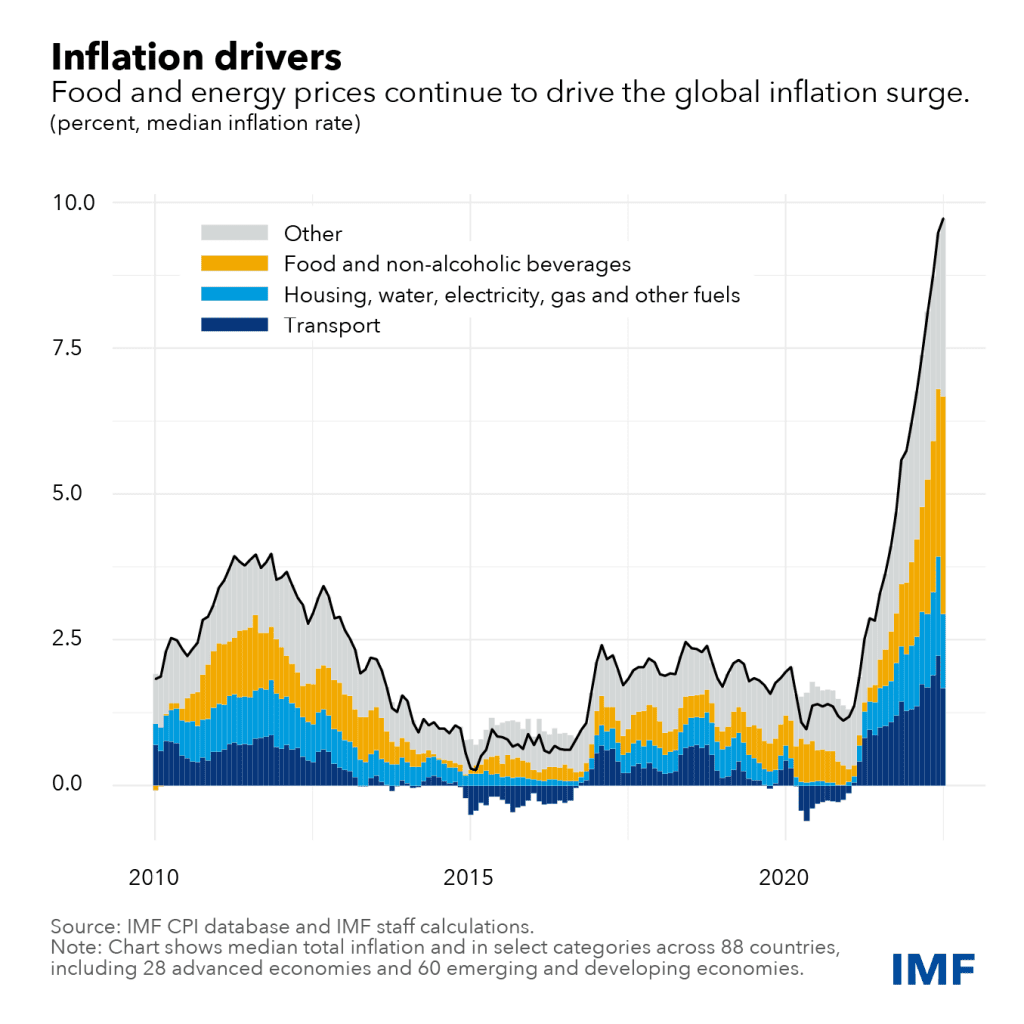

There are four main catalysts of inflation: surging costs of production, swelling national demand, a surplus in the money supply, and an insufficient demand for money. That both the developed and developing world have experienced rising prices since early 2022 points to underlying causes that defied borders. The predominant theory shared by think tanks, academics and central banks is that the current global inflationary crisis is a supply-side issue that has been exacerbated by high costs of production and a surging dollar.

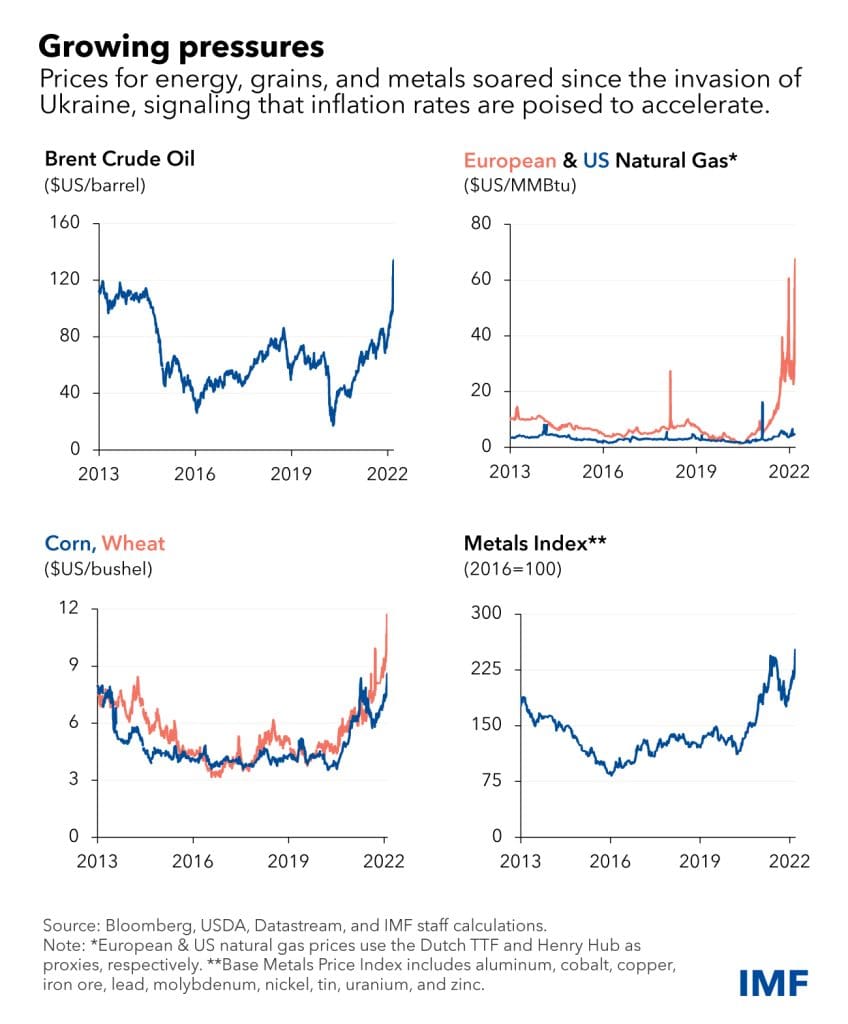

The pivotal moment was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Both countries major exporters of food, fuel, and fertilizer, their conflict led to the shutdown of several ports, in turn leading to higher shipping costs due to time delays, congestion and a scarcity of containers. Within six months of the invasion, natural gas prices had risen by 130% and coal by 120%. Without Ukraine’s exports, prices of wheat, maize and corn skyrocketed.

While the impact was felt the world over, African and the Middle Eastern countries relying on Russian and Ukrainian grain (in some cases to support 50% of domestic consumption) were arguably the most disadvantaged. The alarming rise in energy prices strained economies like Bangladesh that rely on imported petroleum, LNG and coal to fuel major economic activities.

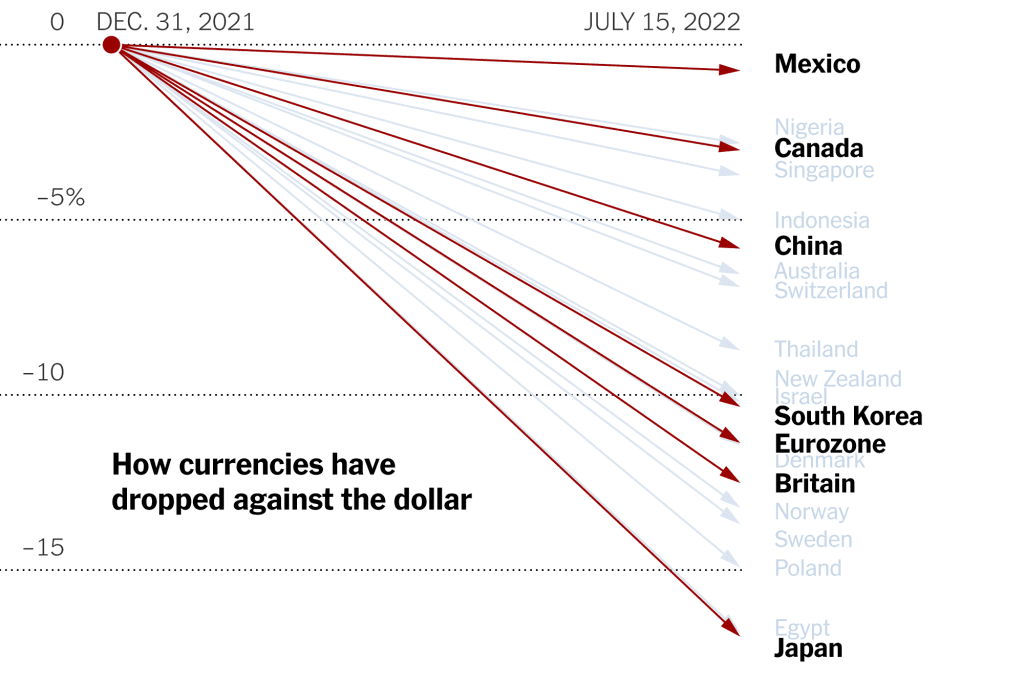

This situation was compounded by the American response. In an attempt to curb rising prices and attract capital, the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates at an unprecedented rate. The ensuing surge in dollar value helped the United States by triggering capital inflows but weakened poorer economies worldwide due to the lower value of their own currencies. Since most imported commodities are priced in the US dollar, developing countries en masse faced a further increase in domestic prices. Bangladesh’s reliance on imports was sharpened by low domestic productivity in agriculture and a lack of suitable substitutes.

Bangladesh’s Response

The nation’s central bank must now navigate a tricky route. The standard prescription for inflation – higher interest rates and a tighter monetary policy – comes with the risk of stagnating the impressive growth the nation has reported in recent years. As such, Bangladesh Bank, in its half yearly Monetary Policy Statement, has committed itself to a multipronged approach that endeavors to simultaneously dampen excessive demand for imports, support activities that produce import substitutes, promote export-oriented industries and catalyze inward remittances.

Some of the key tools deployed by the central bank since July 2022 to achieve this objective deserve consideration:

- Increasing the repo rate: discourages banks from borrowing funds from the central bank, making loans more expensive. The resulting slack in investment helps in controlling inflation

- Relaxing lending cap rate for consumer loans: dissuades loans and dampens economic activity, thereby reducing inflationary pressures

- Extend substantial financing opportunities for firms in the agriculture, SME, import substitute, and export-oriented space

- Increase Letter of Credit margin requirements for luxury and non-essential imported products

The central bank expects domestic prices to fall and the exchange rate position to improve in the coming months, basing their prediction on anticipated gains in agriculture, inward remittances and exports. It concedes that three factors outside of its control can delay progress: the continuing effects of the Russia-Ukraine War, further interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve, and the return of Covid-19 in China.

While the $4.7 billion IMF loan ensured Bangladesh has the funds to finance imports and dictate monetary policy, the conditions attached to the loan complicate the way forward. Some of the mandated reforms are long overdue: simplifying the tax code, expanding social welfare programs, shifting to an interest rate corridor, and reducing non-performing loans in the banking sector. But other conditions, while effective against inflation, have a worrying and extensive track record of stifling domestic growth by lowering governmental spending, increasing taxation, and liberalizing trade. Given that the IMF has already set lofty tax revenue collection targets, the government must hasten to increase the tax base while ensuring that the nation’s middle and lower classes are not made to bear the burden.

While the outlook on inflation remains unclear, there is scope for optimism. Bangladesh’s ambitious monetary policy requires better governance and the IMF conditions demand a cautious approach if the nation is to stabilize prices without losing the gains made in the last decade. In my opinion, demonstrating the country’s capability in handling a global inflation crisis will do more to substantiate Bangladesh’s claim as a newly minted developing country than the expected graduation from the UN’s list of Least Developed Countries in 2026.

Cover Photo: Housing activists march across town toward New York Gov. Kathy Hochul’s office, calling for an extension of pandemic-era eviction protections, Tuesday, Aug. 31, 2021, in New York. Prices paid by U.S. consumers jumped in December 2021 compared to a year earlier, the latest evidence that rising costs for food, gas, rent and other necessities are heightening the financial pressures on America’s households. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer, File)

About the Author

Samiul Karim graduated from Princeton University with an AB degree in Economics. He co-founded and ran a wealth intelligence and business analytics start-up in New York City between 2013 and 2022. A lifelong debater, he represented Bangladesh at the World Schools Debating Championships in 2008 and 2009, and the Princeton Debate Panel between 2009 and 2013. He will join Warwick Business School as an MBA student this coming September.