KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Islam in this land has been present for almost one thousand years; however, the celebration of Eid with much festivity and zeal started from the Mughal time.

- There have been multiple initiatives taken, starting from the Faraizi movement to the recent influx of Wahhabi-Salafi indoctrination, to eradicate the idiosyncratic practices of Bengali Muslims regarding Eid; however, they have largely been unsuccessful.

- Eid is transcending religious boundaries and is becoming more of a cultural festival for Bangladeshis, irrespective of religion.

For about 1.9 billion Muslims around the world, Eid ul-Fitr is not only the biggest religious festival but also a time that comes with a myriad of cultural idiosyncrasies as well as festivity. Coming after the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, the festival brings Muslims together. Bangladesh, being a Muslim majority country, has many cultural aspects regarding the celebration of Eid ul-Fitr, which have been evolving with every generation.

Inception and Start of Muslim Rule

It is widely accepted that Islam first got a foothold in Bengal during the Pala period, due to increased trading with the Abbasid Caliphate. The coastal areas of south-eastern Bengal had a huge Arab merchant presence at the time. The merchants settled and married local women, giving rise to some of the earliest Muslim communities in the region of Bengal. The presence of a small Muslim community in the aforementioned region was first mentioned by the Baghdadi historian and geographer Al-Masudi in his work, The Meadows of Gold.

Bengal was part of one Muslim polity or another without interruption from 1204–1757 CE. The process commenced with the dethronement of Lakshman Sen by Ikhtiyar al-Din Muhammad Bakhtiyar Khilji, resulting in the end of the Hindu Sena Empire. This culminated in many Islamic preachers coming to Bengal and many Bengalis adopting the Islamic religion. The community gradually started developing its own cultures and traditions, which were very similar to those of neighbouring religions as Islam in Bengal took on a syncretic form. However, before the creation of the Bengal subah or province by the Mughals, the celebration of Eid was not that common among the Muslims, as they were very small in number and concentrated in the rural areas. Most of the indigenous inhabitants of Bengal were adherents of Dharmic religions (namely, Hinduism and Buddhism) and local paganism.

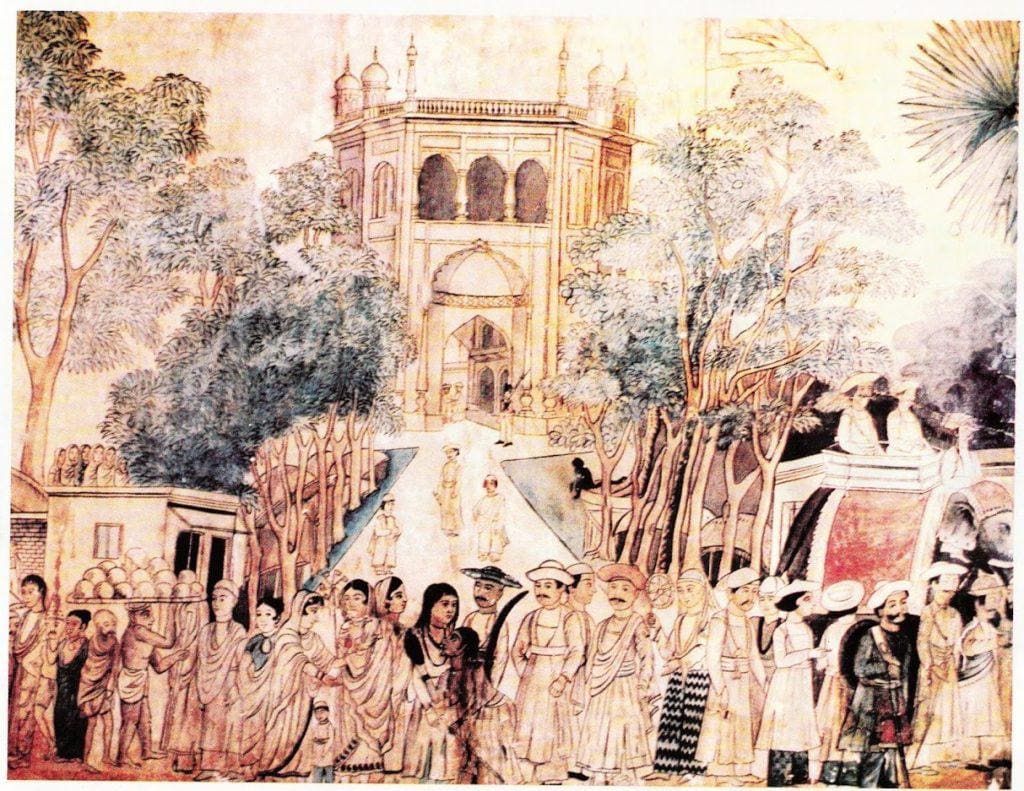

Mughal Bengal

Bengal became a Mughal subah in 1576 CE, and going by the accounts of many historians, it was considered to be the golden age of Bengal. It was also roughly the time when Eid began to be celebrated with pomp and grandeur in much of Bengal. The 1500s were a period when the Muslim population of Bengal rose exponentially, especially in the eastern part of Bengal, coinciding with the present-day territory of Bangladesh. The drainage pattern of the river Ganga altered, and the majority of its water started to go into the river Padma, making the previously forested East Bengal suitable for habitation, and as a result, many new settlements were created that comprised a large number of Muslims.

The oldest documented manuscript related to Eid celebrations in present-day Bangladesh is the work of Mirza Nathan, who was at Bokai Nagar at the time. He wrote that after getting the confirmation of Eid through witnessing the “Eid er Chand” by candlelight, the Mughal army posted in Bengal used to blow trumpets as well as use celebratory gunfire. The common people also used firecrackers.

On Eid Day, Muslim men and women used to wear good clothes, and alms were given out to poor families by the affluent, a tradition that has continued to this day. The Mughal traditions are also largely visible in our Eid cuisine, as it is stacked with many Mughlai dishes, such as polao and Mughal-style meat curry, as well as various sweetmeats. The Mughal-era Eid celebrations were also inclusive of many fairs and carnivals, as well as recreational events such as canoe sprints. The Mughal traditions continued even into the time of the independent Nawabs, as well as the early period of British rule.

British Colonial Era

The beginning of the British colonial period was, however, detrimental to the exuberant celebrations of Eid-ul-Fitr during the Mughal period, as the start of British rule had a negative impact on the Muslim psyche. There were many reformist movements during that time, allegedly attempting to “cleanse” Islam as was practised by the Muslims of Bengal. It was seen as too syncretic by many clerics. Notable among these movements is the Faraizi movement, undertaken by Haji Shariatullah in 1819, which resulted in the eradication of a lot of practices from the Eid-ul-Fitr celebrations in rural Bengal as they were considered to be sinful. However, many Muslim aristocratic families, such as the Nawabs of Dhaka, maintained the traditions of the Mughal era, something that continued till the partition of India in 1947 and well into the early period of Pakistan.

Pakistani Period to Present Era

The Pakistani period saw celebrations of Eid-ul-Fitr becoming more urbanized, as for the first time a large Bengali Muslim middle class population had come up. However, the repressive attitude of successive regimes towards Bengali culture and state policy that emphasized stricter interpretations of Islam did away with a lot of practices from the urban Muslim populace of Bangladesh. In the 1980s, a decade after the liberation of Bangladesh, there was a surge of Wahhabi and Salafi practices in Bangladesh due to the influx of Arab petrodollars, which placed curbs on a lot of practices like the use of firecrackers and extensive carnivals that, however, didn’t become successful on a large scale.

For the urban as well as suburban populace of the 1980s and 1990s, Eid started with the sighting of the moon. Each locality had children and young adults exploding firecrackers, which are colloquially known as “baji,” with “Chand Raat” or the sighting of the new moon being a more exciting time for the younger members of a family. Eid day started with the members of a family partaking of sweetmeats before going to attend the Namaz of Eid, which ended with everyone embracing one another, which is colloquially known as “Kolakuli.” The younger members of the family demanded or expected “Salami” or “Eidi” from the older members, who obliged, in line with tradition.

This was followed by visits to the houses of many relatives as well as relishing the delicious dishes that have been part of Bengali heritage since Mughal times. The evenings were a time when all the family members gathered together to watch television programs. Through the 1980s and much of the 1990s, the state-owned Bangladesh Television was the sole TV channel in the country. It used to air many soap operas as well as programs such as “Ityadi,” which have remained ingrained in the minds of people from that generation.

The situation began to change in the 2000s, as there was more digitalization and many more sources of entertainment, including quite a few new, private TV channels coming up. Cultural dynamics also began to change with the gradual break-up of joint families and the creation of nuclear families. The 2000s until now have seen the continuation of that trend. With even more digitalization, people have been spending more Eid time on social media sites than before.

An Optimistic Future

Eid-ul-Fitr is no longer confined to Muslims but has rather become a festival that has transcended the boundaries of religion to become a truly national festival in the context of Bangladesh. Although fundamentalist forces have been trying to force an end to the practices that have been native to this region and replace them with ones that have no cultural affinity with Bangladesh, they have not succeeded in their aims. For the future, it is our wish that Eid-ul-Fitr celebrations in Bangladesh remain synonymous with Shemai-Firni, Atoshbaji, and Salami and not with practices that originated far from the fertile land of Bengal.

About the Author

Rassiq Aziz Kabir is a final-year student of Economics at the University of Dhaka. Rassiq also works as a freelance contributor for the English daily, The Financial Express.