Rohingya refugees have been repatriated from Bangladesh previously, but not following due process, without adhering to the international laws. The Rohingya refugee problem needs a sustainable solution, unlike the previous attempts taken by the BNP government.

August 25, 2023 marked the sixth anniversary of the largest forced displacement of the Rohingyas from Myanmar’s Rakhine state into Bangladesh’s coastal town of Cox’s Bazar. The persecuted Muslim minority group, in the name of ‘clearing operations’, were subjected by the infamous Tatmadaw to what the then UN human rights chief describedas ‘a textbook case of ethnic cleansing’. Since 2017, many countries and organizations, including the U.S., have recognised that the crimes committed against the Rohingyas indeed qualify as genocide and crimes against humanity. Proceedings against Myanmar for their grave crimes against the Rohingyas are currently ongoing at the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Bangladesh, despite being a non-signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol (and without specific legislation to address refugee issues), became one of the most important refugee-hosting states in the world when it allowed close to 750,000 Rohingyas to take shelter from the violence unleashed on them in Rakhine in August 2017. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s Government and the people of Bangladesh received global recognition for their humanitarian gesture in opening their doors and arms to the persecuted group. At present, Bangladesh is hosting more than 1.2 million Rohingyas (including those from earlier exoduses).

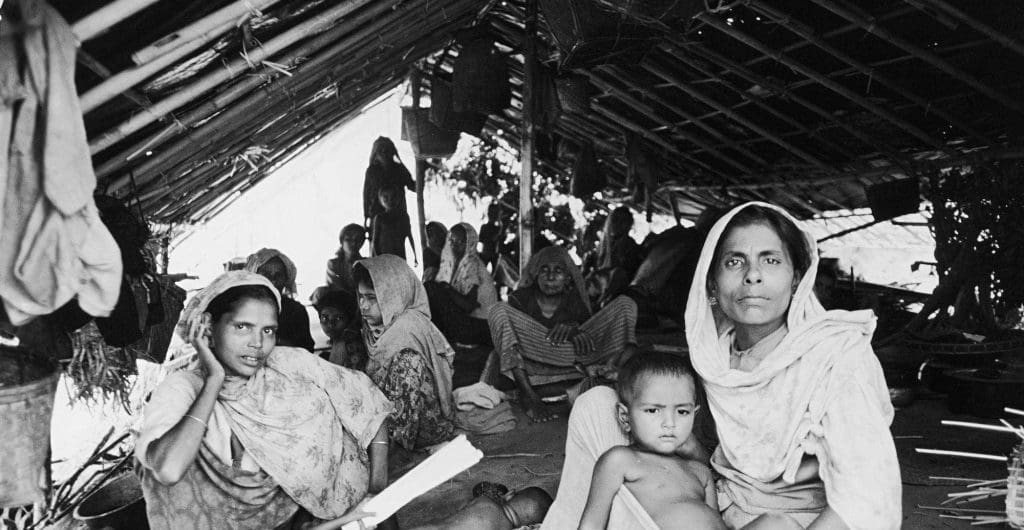

A Rohingya Refugee camp in Bangladesh, 1978. © MSF (Medecines Sans Frontieres/Doctors without Borders)

This was however, not the first time that the Rohingyas have been driven out of their homeland in Rakhine and into Bangladesh. In 1977-78, around 200,000 Rohingyas, having been subjected to ‘mass arrests, persecution, and horrific violence’, fled into neighbouring Bangladesh. In 1989, in another fresh round of persecution, including ‘compulsory labor, forced relocation, rape, summary executions, and torture’, around 250,000 Rohingyas were forced to take shelter in Bangladesh. And it is regarding these two earlier instances of Rohingya exodus and their subsequent repatriation to Burma/Myanmar, which is the focus of this paper.

BNP and Tarique Rahman’s Comments

On August 25, marking the sixth anniversary of the latest Rohingya exodus, the Acting-Chairman of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), Tarique Rahman wrote a post in his verified Twitter/X account on the repatriation. The following text is the main point of his post: “On the Sixth Genocide Remembrance Day, we stand together with the Rohingya refugees in sympathy and solidarity. The repressed refugees are far from returning to their homeland, while President Ziaur Rahman and Prime Minister Khaleda Zia sheltered them, mounted global pressure on Myanmar, and conducted successful repatriations”.

The BNP itself made a similar post on the same day, which claimed that their founder General Ziaur Rahman repatriated the Rohingyas in 2 years (as regards the 1977-78 exodus), and Begum Khaleda Zia repatriated them in 3 years (as regards the 1989 exodus). In both these posts, the party and its absentee, fugitive leader used the two earlier instances of repatriation as successful diplomacy by different BNP governments.

Principle of Non-Refoulement

Refugee law scholar M Sanjeeb Hossain, in an article for the Oxford Journal of Refugee Law, notes; ‘There is a broad consensus amongst refugee law scholars that the principle of non-refoulement, the cornerstone of refugee protection enshrined in Article 33 of the 1951 Refugee Convention, is a norm of customary international law’. What does this mean? According to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (OHCHR), non-refoulement is a principle which:

“…prohibits States from transferring or removing individuals from their jurisdiction or effective control when there are substantial grounds for believing that the person would be at risk of irreparable harm upon return, including persecution, torture, illtreatment or other serious human rights violations.”

Customary international law refers to international obligations arising from established international practices, as opposed to obligations arising from formal written conventions and treaties. Customary international law results from a general and consistent practice of states that they follow from a sense of legal obligation (see Chapter II, Article 38 of the ICJ Statute)

Current Bangladesh Position

Now that we know what the principle stands for, and the binding nature of the obligation it imposes, an example will illustrate this principle in operation. It is widely accepted by the international community that the current situation in Myanmar generally, and the Rakhine state in particular, are not conducive to the return of the Rohingyas. This is because, even the 600,00 or so Rohingyas who remain in Myanmar at present, are subjected to ‘persecution and violence, confined to camps and villages without freedom of movement, and cut off from access to adequate food, health care, education, and livelihoods’. The situation is further exacerbated by the fact that currently Myanmar is again under the grips of an all-powerful military junta, which is waging a brutal war against its own people.

If the Government of Bangladesh were to forcefully repatriate the Rohingyas into Myanmar despite knowing the dangers they face upon return, that is very likely to be a breach of the customary int’l law regarding non-refoulement. Fortunately, that has not been the case so far. Despite repatriation being central to Bangladesh’s policy on the Rohingyas, the government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been consistent on their pledge to only facilitate ‘safe, voluntary, and dignified’ repatriation.

Yet, that is precisely what the BNP and its acting-chair seem to be criticising the Awami League Government for. To enunciate their point, they are using the earlier instances of repatriation under the Ziaur Rahman and Khaleda Zia governments as success stories. Thus, it is imperative to examine the circumstances under which the earlier “successful” Rohingya repatriations took place.

Repatriations: BNP Governments

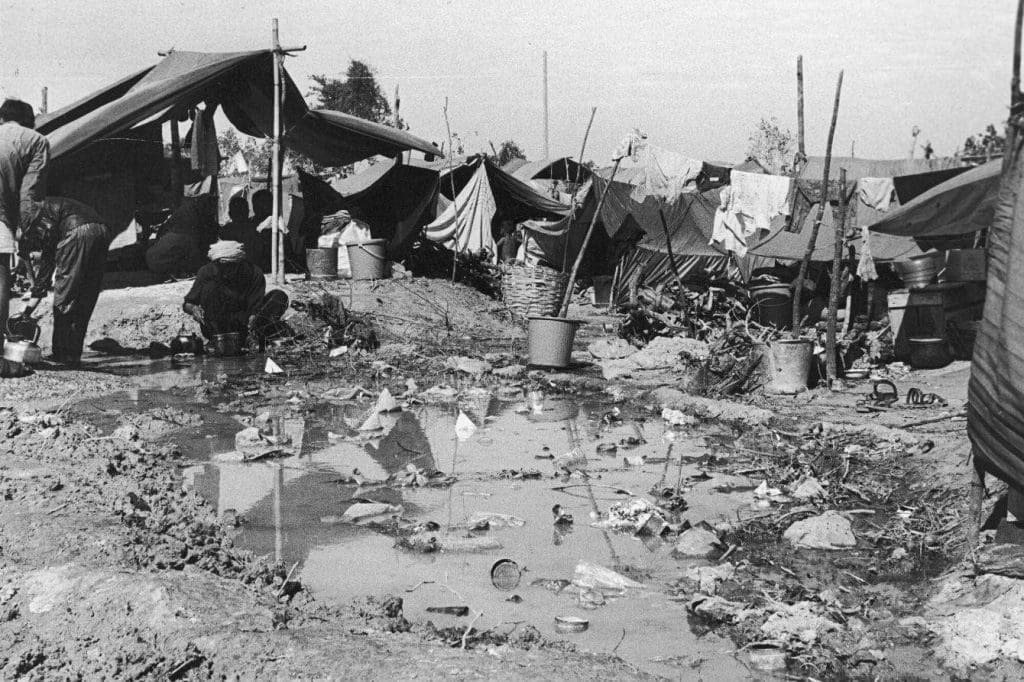

Jeff Crisp of the Oxford Centre for Refugee Studies, in an article for the Humanitarian Exchange, summarised the findings of hitherto unpublished documents from UNHCR on the previous two repatriations of the Rohingyas under the governments of General Ziaur Rahman and Begum Zia. In the 1978 repatriation, the following tactics were used to force or compel the Rohingya to leave the camps in Bangladesh: Attacks on the Rohingyas by Bangladeshi security personnel and government officials resulting in a number of deaths, and withholding food and other essential assistance from the refugees.

Once the repatriation was completed, the UNHCR found that a majority of the 10,000 Rohingya deaths in the preceding two years were due to severe malnutrition resulting from food shortages. The duress/compulsion tactics consciously employed by the Bangladesh authorities at that time completely negated the ‘voluntariness’ of the repatriation. The fact that within four years of the hurriedly carried out repatriation, a new law by the Burmese authorities effectively excluded the Rohingyas from citizenship, and a new phase of mass atrocities were unleashed on them within a decade, speaks volumes about the sustainability of the Ziaur Rahman government’s ‘successful’ repatriation.

The repatriation under Begum Zia’s government also had similar allegations of compulsion and duress. There was ample evidence with UNHCR to suggest that the Bangladesh authorities used physical and psychological harassment against the Rohingyas to compel them to go back. At one point, the situation became so that UNHCR decided to leave the process altogether. Another tactic employed during that time included stipulating a fixed timeline for repatriation notwithstanding the conditions which awaited the Rohingyas in Myanmar. The voluntary, safe, and dignified aspects of the process were fully absent. M Sanjeeb Hossain writes, ‘These forced repatriations took place in premature, involuntary and unsafe conditions in violation of the principle of non-refoulement’.

‘These forced repatriations took place in premature, involuntary and unsafe conditions in violation of the principle of non-refoulement’.

M Sanjeeb Hossain

Director, Research, CPJ BRAC University

Way Forward

There is no denying that the repatriation of the Rohingyas is politically significant for Bangladesh. A recent survey by the Washington-based International Republican Institute (IRI) revealed that on the Rohingya crisis, 68% Bangladeshis feel that they should be repatriated to Myanmar immediately, with only 26% feeling that the Rohingyas should stay in Bangladesh until it is safe for them to return. Undoubtedly, BNP and its Acting Chair’s posts are intended to tap into that base political sentiment. Will this impact the position of the government of Bangladesh?

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s Government, despite negotiating repatriation efforts with the help of China and UNHCR, has so far resisted the domestic pressure to send the Rohingyas back without such efforts being voluntary and safe. This is particularly impressive given that this time around, the number of Rohingyas sheltered in Bangladesh is the highest ever, and more than six years has passed since the latest exodus.

However, with the nat’l election fast approaching, deteriorating law and order situation in the camps, the government of Bangladesh spending 1.2 billion USD annually for the refugees despite facing economic issues of its own, and devastating food ration funding cuts from the int’l donors, it is difficult to say how long the Hasina government can resist such pressures. The last thing the Rohingyas need is their repatriation (voluntary or not) becoming a key point in the election campaign of the opposition. Int’l partners should therefore, raise this issue with the BNP, as they always do with the government, and make it clear that, without voluntariness and genuine assurances of safety upon return, any repatriation would likely breach the principle against non-refoulement, and thereby breach int’l law.

The cover photo “Bangladesh 1992 © Liba Taylor” is used with permission of the photographer

About the Author

Shah Ali Farhad is the founder and publisher of the Confluence. He is a lawyer, policy-researcher, and political activist. He is currently engaged with the Dhaka-based think-tank, the Centre for Research and Information (CRI), as its Senior Associate. He is an advocate of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh and a Barrister of the Lincoln’s Inn, UK. He previously served as a Special Assistant to the Prime Minister of Bangladesh. He holds a masters of public policy (MPP) from the University of Oxford, and a masters in human rights law (LLM) from the University of Hong Kong.