Digital Security Act has been the talk of the town for a long time. Should DSA be abolished or reformed?

Bangladesh is currently going through a digital revolution, with the country rapidly embracing digital technologies and services. The government has implemented several initiatives to promote the use of technology and to make digital services more accessible to the general public since 2009. Overall, the digital era in Bangladesh is helping to transform the country’s economy and society, making it more connected, efficient, and inclusive.

As we are living in an era of unprecedented technological advancement. Our lives are deeply intertwined with the usage of digital technology and the internet. The internet has brought us many benefits, including instant communication, access to information, and opportunities for business and for education and so on. However, with these benefits also come risks. The internet has created new avenues for criminal activities, such as identity theft, fraud, cyberbullying, disseminating misinformation, spreading fake news and hate speech to make the society unstable.

Bangladesh is not immune to these risks either. In fact, as one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, Bangladesh is increasingly reliant on digital technology to drive growth and development. As more people in Bangladesh go online, the risks associated with the internet become more acute. It is, therefore, essential that we consider the importance of the role of digital security laws in Bangladesh in this current digital era.

With regard to the digital security laws in Bangladesh, on one hand, some argue that digital security laws are necessary to protect citizens and businesses from cybercrime. These laws can provide a framework for prosecuting cybercriminals and preventing future attacks. Digital security laws can also provide guidance for businesses on how to protect their customers’ data and ensure their cybersecurity practices are up to par. In addition, digital security laws can help build confidence in the use of technology and the internet, which is essential for continued growth and development; and overall for keeping a secured digital environment.

On the other hand, opponents of digital security laws argue that they can be used to throttle free speech and limit access to information. This leads to the limitation of the potential for innovation and creativity. In addition, opponents also argue that digital security laws may be difficult to enforce, particularly in a country like Bangladesh, where resources and infrastructure may be limited.

Therefore, it is now the right time to develop an intellectual discourse on digital security laws to foster trust, security, and stability in the digital environment.

The Digital Security Act, 2018 “DSA” was passed by the Bangladesh Parliament in October, 2018 to regulate digital activities and provide security in the digital era. The act aims to address a range of digital offenses, including cybercrime, online defamation, hate speech, and other forms of digital crimes. However, the law has been criticized by human rights groups and journalists for being excessively broad and potentially leading to censorship and violating freedom of expression. This article aims to critically analyze the DSA, its effectiveness in ensuring digital security in Bangladesh, and suggests ways to amend the law to address its shortcomings. The article explores the positive aspects of the DSA while also considering the concerns raised by its critics. By examining the DSA in the context of digital security in Bangladesh, this article contributes to the ongoing debate on the balance between digital security and freedom of expression in the digital era.

Regulating Cyberspace: Historical View-Points

As digital technology has developed and reached the hands of the public, states have realized the growing need to regulate the internet. However, there has been a consistent resistance against internet regulation beginning from the first inception of such laws. Singapore was the first country in the world to regulate the internet through the Computer Misuse Act, 1993. It faced significant opposition and criticism from the cyberlibertarian movement for being too broad and its potential to stifle free speech. Similarly, when the USA enacted the Telecommunications Act of 1996, it caused heavy criticism and the publication of ‘A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace’ by American poet, essayist, and cyberlibertarian activist John Perry Barlow in opposition of governments trying to regulate the internet.[2] The declaration started with the provocative line –

‘Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather. In China, Germany, France, Russia, Singapore, Italy and the United States, you are trying to ward off the virus of liberty by erecting guard posts at the frontiers of Cyberspace. These may keep out the contagion for a small time, but they will not work in a world that will soon be blanketed in bit-bearing media.’’

John Perry Barlow

American poet, essayist, and cyberlibertarian activist

The declaration was grounded on the contemporary debate whether actions in the ‘cyberspace’ inherently removed the physical world and whether states have the jurisdiction to regulate the internet. In the Declaration, Barlow asserted the idea that governments had no legitimate authority over cyberspace and that it should be a space free from government control. He argued that the internet represents a new kind of social space, separate from physical space, and that it should be governed by its own set of principles.

But by 2023, we’ve moved a long way from such debates from the early internet era. It is well established that the internet can be used to commit crimes that have harmful consequences in the ‘physical’ world. From hacking to fraud, identity theft to hate speech, there are virtually infinite types of crimes that can happen through the internet. Criminals can also use the internet to facilitate their otherwise physical crime. Therefore, the need for governments to regulate the use of the internet within their own jurisdiction is firmly established. But fragments of the cyberlibertarian philosophy are still present today. Criminalization of online activity is frowned upon by civil society and activists around the world and Bangladesh is no exception to that.

The Digital Security Act, 2018: A Legal Analysis

The Digital Security Act, 2018, criminalizes a wide range of digital offenses, including cyberbullying, spreading fake news or propaganda, defamatory content, and unauthorized access to computers or networks. The law provides for imprisonment up to 14 years and fines up to BDT 25 lakhs (approximately USD 30,000) for offenses related to digital activities. The act also includes several provisions that allow law enforcement agencies to search and seize digital devices without a warrant.

DSA has various provisions to protect the rights and integrity of people against online crimes. The remedy against such crimes mainly comes from criminal proceedings against the perpetrator. The act also requires the government to set up an emergency response team to deal with cyber-attacks and a forensic lab to examine evidences

Protecting Digital Rights:

DSA ensures the protection of citizens’ digital rights. The act includes provisions for the protection of personal data, freedom of expression, and privacy. Section 28 of the act prohibits the unauthorized collection, use, or disclosure of personal data, while Section 31 protects freedom of expression on digital platforms. The act also prohibits the use of digital platforms for blackmail, defamation, or harassment.

Preventing Cyber Crimes:

DSA aims to prevent cybercrimes such as hacking, cyberbullying, and online fraud. The act includes provisions for the punishment of cybercriminals, such as fines and imprisonment. Section 17 of the act prohibits hacking, while Section 25 prohibits the creation or dissemination of fake news or defamatory rumors. Section 22,23 and 24 of the act also includes provisions for the punishment of online fraud, counterfeit and identity theft. Section 8 of the act criminalizes the spreading of propaganda and false information that can disrupt law and order or harm the image of the state. Section 28 of the act criminalizes unauthorized access to computer systems, data theft, and the use of computer systems to commit offenses.

Ensuring Security of Digital Platforms:

DSA ensures the security of digital platforms by requiring service providers to take necessary measures to protect users’ data. Section 25 of the act requires service providers to remove or block access to content that is deemed harmful to national security, public safety, or religious sentiments. The act also requires service providers to provide information to law enforcement agencies if required.

Non-DSA Cyber Security in Bangladesh

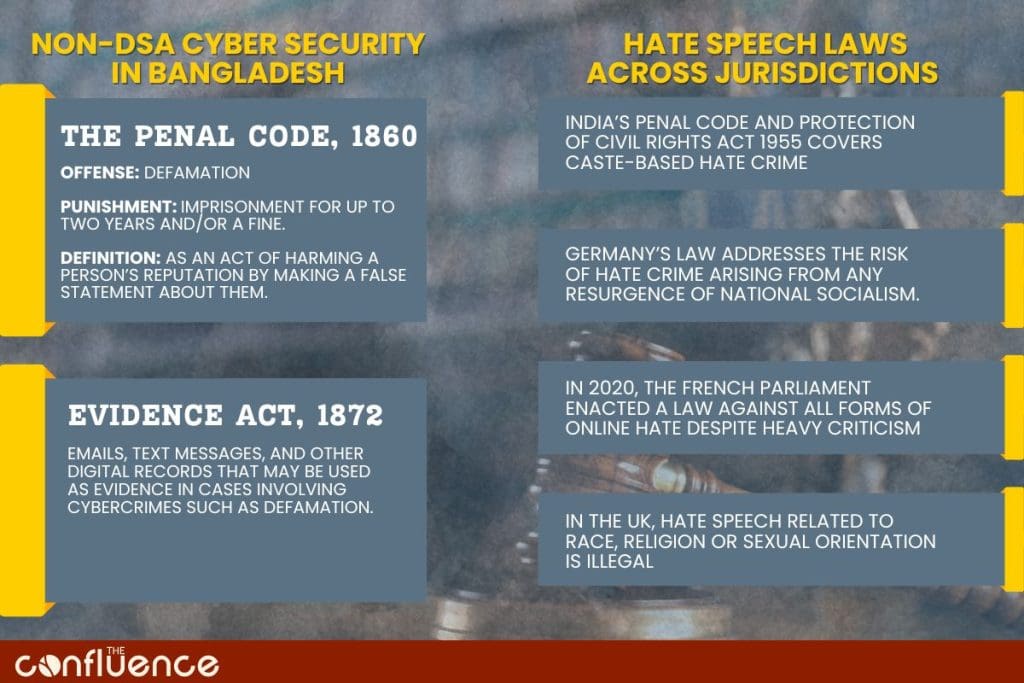

Cybersecurity protection in Bangladesh is not limited to just the DSA as there are other laws that provide some level of protection against cybercrimes such as defamation.

The Penal Code, 1860 includes provisions on defamation. Under section 499 of the Penal Code, 1960; defamation is a criminal offense that can result in imprisonment for up to two years and/or a fine. Section 500 of the Penal Code, 1860 provides a definition of defamation as an act of harming a person’s reputation by making a false statement about them.

Furthermore, the Evidence Act, 1872 provides a mechanism for the admission of electronic evidence in court proceedings. This includes emails, text messages, and other digital records that may be used as evidence in cases involving cybercrimes such as defamation.

Now the question, whether cyber security can be ensured in Bangladesh by the application of Defamation Law under the Penal Code, 1860? The answer would be, NO- cyber security cannot be practically ensured in Bangladesh by the application of the law of defamation alone. Cyber security is a complex issue that requires a multifaceted approach, including technical measures such as firewalls, encryption, and secure coding practices, as well as legal and regulatory frameworks that provide for the protection of data and the punishment of cyber criminals.

While defamation laws can be an important tool for protecting individuals and organizations from false or damaging statements made online, they are not sufficient to ensure cyber security on their own. Cyber security requires a comprehensive strategy that involves a range of measures, including education and awareness campaigns, partnerships between government and private sector stakeholders, and the development of robust incident response plans through a solid legal framework.

In addition, cyber security threats are constantly evolving, and new threats emerge all the time. This means that a successful cyber security strategy must be dynamic and adaptable, with ongoing efforts to identify and mitigate new threats as they arise.

Furthermore, in Bangladesh, the civil courts are hugely overburdened with cases in excess of their capacity. In such a situation, defamation suits get lost in the riddle of proceeding without the victims getting the adequate remedy they are entitled to by the law. Unlike in the first world countries where the defamation regime is strong to regulate institutionally spread rumors, misinformation projects or rhetoric attacks against women and children, Bangladesh needs an alternate strong legal instrument to regulate such activities.[1] The government considers the DSA to be the capable candidate to fill that role. Moreover, many jurisdictions around the world acknowledge that defamation law is solely not enough to regulate online hate speech and its consequences. Thus, they have additional penal provisions alongside defamation laws to prevent hate speech.

Hate Speech Laws Across Jurisdictions

Usually, these laws are focused on the types of the hate speech most prevalent in the history and prevalent culture of that country. For example, India’s penal code and protection of civil rights act 1955 covers caste-based hate crime. On the other hand, European laws are more focused on antisemitism and racism in consideration of their track record in that regard. Germany’s law addresses the risk of hate crime arising from any resurgence of National Socialism.[2] In 2020, the French parliament enacted a law against all forms of online hate despite heavy criticism.[3] In the UK, hate speech related to race, religion or sexual orientation is illegal.[4]

DSA of Bangladesh also attempts to deter online hate speech. Specifically, online spaces in Bangladesh are prone to gender-based hate speech. Hate speech regarding minorities and religion are also very common in Bangladesh, especially in the social media. These projection of toxicity results in victim blaming, riots, crimes including rape and other social problems.[5] Therefore, it’s not unreasonable for DSA to regulate online speech to some extent. But nevertheless, DSA has its shortcomings in the approach it takes.

In summary, while defamation laws can play a role in protecting individuals and organizations from online harm to a limited number of populations, they are not sufficient to ensure cyber security in Bangladesh or any other country. A comprehensive approach to cyber security is required, including technical measures, legal and regulatory frameworks, and ongoing education and awareness efforts.

Laws Similar to DSA in South Asia

Several countries in South Asia have enacted legislation similar to DSA to address digital security threats. Some of these acts are:

Information Technology Act, 2000 (India): The Information Technology Act, 2000 is a law enacted by the Government of India to regulate e-commerce and to provide legal recognition for transactions carried out electronically. The act includes provisions to deal with cybercrime, including unauthorized access to computer systems, hacking, and data theft.

Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016 (Pakistan): The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016 is a law enacted by the Government of Pakistan to regulate cybercrime and digital security threats. The act includes provisions to deal with offenses such as unauthorized access, cyber terrorism, and cyber stalking.

Electronic Transaction Act, 2008 (Nepal): The Electronic Transaction Act, 2008 is a law enacted by the Government of Nepal to regulate electronic transactions and to provide legal recognition for digital signatures. The act includes provisions to deal with cybercrime, including hacking, data theft, and identity theft.

The DSA and the similar acts in South Asia have several similarities and differences. Some of these are:

Scope and Definitions

The DSA covers a broad range of offenses related to digital security, including unauthorized access to digital devices, data theft, and defamation. The act also includes provisions to deal with offenses related to spreading false information, propaganda, and hate speech. The act defines digital devices, data, and other key terms, and provides guidelines for their interpretation.

The similar acts in South Asia also cover similar offenses related to cybercrime and digital security threats. However, the scope and definitions vary from country to country. For example, the Information Technology Act in India primarily deals with e-commerce and transactions carried out electronically, while the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act in Pakistan focuses more on cyber terrorism and unauthorized access to critical infrastructure.

Penalties and Punishments

The DSA provides for severe penalties and punishments for offenses related to digital security. Offenders can face imprisonment for up to 14 years and fines of up to BDT 10 million (about USD 118,000). The act also includes provisions to deal with organizations and institutions responsible for digital security breaches, which can face fines of up to BDT 25 million (about USD 295,000).

The similar acts in South Asia also provide for severe penalties and punishments for cybercrime and digital security offenses. For example, the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act in Pakistan provides for imprisonment for up to seven years and fines of up to PKR 10 million (about USD 62,000) for unauthorized access to computer systems.

The Criticisms of the DSA

The DSA’s broad and vague language has been criticized by human rights groups and journalists, who argue that it violates freedom of expression and could be used to suppress dissent. Despite these criticisms, the government of Bangladesh has defended the law as necessary to ensure digital security and combat cybercrime. The DSA has been used to prosecute and convict individuals for various digital offenses. According to a report by the Bangladesh Center for Development Journalism and Communication (BCDJC), more than 1,000 cases have been filed under the DSA since its enactment, and several individuals have been sentenced to imprisonment and fines.

Critics of DSA argue that the act is open to abuse and that it violates the right to freedom of expression and the right to privacy. However, the Constitution of Bangladesh recognizes freedom of speech as a fundamental right of its citizens and like in many other countries, this right is not absolute and certain limitations are imposed on it to ensure that it does not cause harm to the society. The constitution of Bangladesh recognizes the importance of a balance between the freedom of speech and expression and the need to protect public order, decency, morality, and national security. These limitations on freedom of speech are necessary to protect the rights and interests of others and to prevent any damage or harm to society. Therefore, the government can also impose reasonable restrictions on freedom of speech and expression to maintain public order, morality, and decency. For example, the government can regulate the use of public spaces for rallies or demonstrations to prevent any disruption of public order.

Another primary concern with the DSA is that it is too broadly and vaguely worded, leaving room for interpretation and misuse. For example, the act criminalizes the publication or transmission of any material that is deemed to be “fake” or “fabricated.” This provision could be used to suppress legitimate dissent or criticism of the government. However, it is impossible for lawmakers to address every possible scenario or situation that may arise, and so there will always be some ambiguity or uncertainty in the law. In order to address these gaps or uncertainties, the courts are tasked with interpreting and applying statutory law to specific cases. The court’s role is to interpret the language of the law and determine its meaning and application in a particular case. This is why courts play such an important role in our legal system.

Another concern is that the act allows law enforcement agencies to search and seize digital devices without a warrant. In certain situations, law enforcement agencies may need to search and seize digital devices as part of an investigation to prevent digital security threats, such as cyber-attacks, terrorist activities, or other criminal activities.

The Way Ahead for the DSA

As we already know, the DSA in Bangladesh has faced significant criticism from various quarters, including journalists, civil society groups, and human rights activists. While it is important to maintain cybersecurity in the country, it is equally important to ensure that the laws that govern digital security are not misused to stifle dissent or infringe upon individuals’ rights to free expression and privacy in accordance with the constitutional provisions.

However, does it mean abolishing the DSA is the only option left? I would argue that rather than abolishing the act altogether, there may be a need for reforms to address the concerns raised by its critics. Such reforms may include narrowing the scope of the law’s provisions to target only those activities that pose a genuine threat to cybersecurity.

Additionally, the act may need to be revised to ensure that it does not infringe upon individuals’ rights to free expression, association, and privacy. This may involve providing greater protections for whistleblowers, journalists, and other individuals who expose corruption or wrongdoing. Such reforms should be guided by input from stakeholders across civil society, government, and the private sector, and should aim to promote a free, open, and secure digital environment in Bangladesh.

Suggested Reforms for the DSA

To ensure digital security in the digital era, it is essential to have a robust legal framework that protects the rights of citizens while also addressing the challenges of cybercrime and other digital offenses. There needs to be a balance to ensure that provisions of DSA are not misused to silence dissent and criticism. Here are some recommendations for amending the DSA to better address the challenges of digital security in Bangladesh:

Narrowing the Definition of Offenses: The scope of the DSA should be narrowed to focus on specific offenses related to cybercrime, hate speech and digital offenses. The definition of what constitutes offensive or defamatory content should be clarified, and provisions for the spread of false information should be limited to cases where it poses a real threat to public safety or security. This would prevent the arbitrary arrest and detention of individuals and protect freedom of expression.

Protection of Journalistic Activities: The law should provide clear protection for genuine journalistic activities and ensure that journalists and media outlets are not penalized for publishing news and opinions as per the journalistic norm and regulations.

Increased judicial oversight: Judicial oversight in various stages of the investigation should be increased. This will ensure that the law is not misused for political purposes and that there is adequate judicial oversight of its implementation.

Provide clear guidelines for law enforcement agencies: The act should provide clear procedural guidelines for law enforcement agencies on how to investigate and prosecute digital offenses.

Strengthening data protection: The law should include provisions for the protection of personal data and privacy rights. This will help prevent data theft and ensure that individuals’ privacy rights are protected.

Accountability for Misuse/Abuse: Introduce a provision for those who make false accusations under DSA.

Conclusion

Laws like the DSA are necessary for ensuring digital security in Bangladesh. The law includes provisions for the protection of citizens’ digital rights, prevention of cybercrimes, and the security of digital platforms. It is evident that the act is necessary in order to prevent the growing number of crimes using digital devices. However, there is a need to balance freedom of expression with the need to prevent the spread of harmful information. It is crucial that the law’s provisions are not misused to suppress freedom of speech and expression as guaranteed in our constitution. The law should be amended to balance digital security and freedom, and ensure adequate judicial oversight.

Cover photo taken from BDNews24.

About the Author

Arafat Hosen Khan is a Barrister at Law & Advocate of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh. He is currently serving as the Chairman of the Department of Law, North South University. He is also an “O’Brien Fellow” of the McGill Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism at McGill University.

Bibliography

[1] Mohibul Hassan Chowdhoury, ‘With or Without Digital Security Laws in Bangladesh in the Digital Era’, 14 March 2023, North South University, Dhaka (Recorded speech)

[2] Regeln gegen Hass im Netz – das Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz (Act to Improve Enforcement of the Law in Social Networks (Network Enforcement Act, NetzDG), 2017 (Germany)

[3] LOI n° 2020-766 du 24 juin 2020 visant à lutter contre les contenus haineux sur internet (LAW n° 2020-766 of June 24, 2020 aimed at combating hateful content on the internet), 2020 (France)

[4] Public Order Act, 1986 (UK)

1 comment

[…] passed legislation to sustain citizens, revising the ICT Act for safeguarding and instituting the Digital Security Act to tackle digital transgressions. Despite its initial intention, the Digital Security Act has been […]