Ziaur Rahman, Bir Uttam was appointed as army chief of staff, after K M Shafiullah resigned on 15th August, 1975 when Bangabandhu was killed by some military officers. Later he became Chief Martial Law Administrator on 6 November 1975.

On 30 May 1977, political illegitimacy dug deeper roots in Bangladesh. Less than two years after the assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family and the murder of the Mujibnagar leaders in prison, General Ziaur Rahman was on his way to tightening his grip on power.

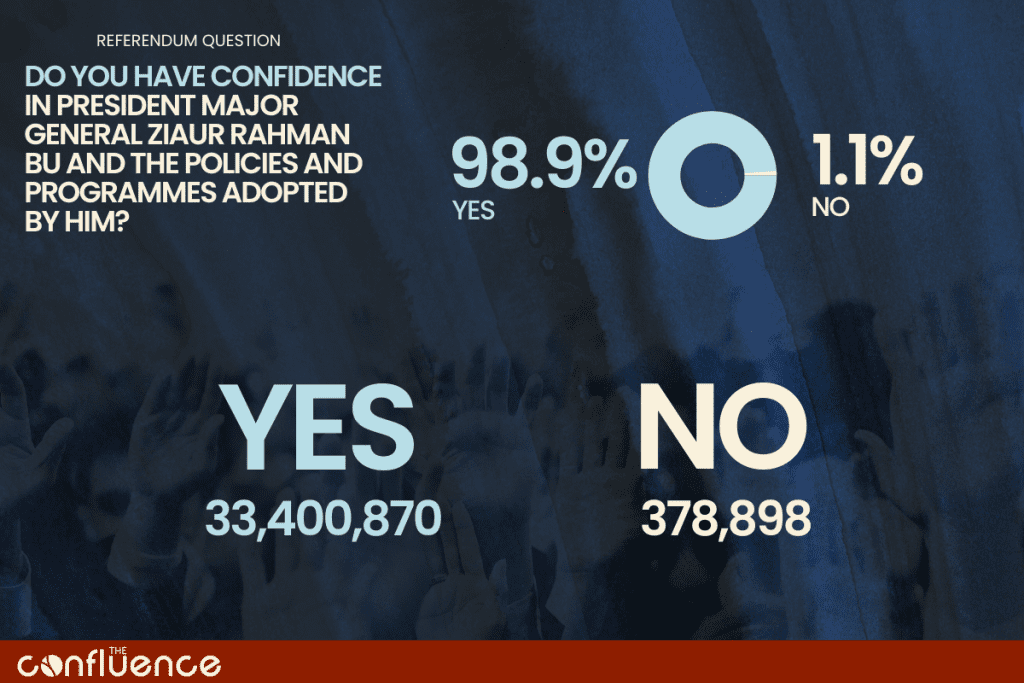

On the day, a so-called referendum Zia had earlier called in order to gain public approval of his seizure of the presidency a month earlier resulted in an improbable outcome. But, again, it was no surprise that Zia and his acolytes claimed that Bangladesh’s first military ruler had obtained 98.8 percent of support from the electorate.

And it was no surprise because the general was simply following in the footsteps of earlier dictators in other countries. Dictators then and later have always had a way of reassuring themselves, through applications of the machinery of disinformation, machinery operated by their sycophants, that they enjoy huge public support.

As the regime was to claim, Zia obtained the support of 33,400, 870 voters. In other words, to the question, ‘Do you have confidence in President Major General Ziaur Rahman BU and the policies and programmes adopted by him?’, all this large segment of the electorate said yes. And the ‘no’ box garnered no more than 378,898 votes, or a mere 1.1 per cent of the vote.

A Field Day Manufacturing Public Support

The surprising bit in the story is that the results of the referendum were placed in the public domain against a background of voting centres remaining predictably empty. No enthusiasm was observed in the country about the vote. Besides, with little opportunity for supporters of the No vote to campaign against the measure, the regime had a field day manufacturing public support for itself.

On 30 May 1977, therefore, Bangladesh was pushed into an area of darkness that was to leave the nation reeling from the wounds inflicted on it by a regime which had already demonstrated a sinister determination to undermine the ethos of the country.

General Zia, having turfed out Justice Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem from the presidency on 21 April – thereby taking a leaf out of the book of Pakistan’s General Ayub Khan, who had removed President Iskandar Mirza at gunpoint in October 1958 before claiming the presidency for himself – needed to acquire some sort of legitimacy for his seizure of power.

The referendum was his way of informing himself that his hold on power had attained a formal structure. But, then again, Zia had exercised power as deputy martial law administrator since 7 November 1975 when his loyalists in the army manoeuvred his rise to the top through the murder of General Khaled Musharraf and two other military officers.

The Power Structure Shaping Up

In the power structure shaping up, though President Sayem was nominally the head of state and chief martial law administrator and the chiefs of the air force and navy served as deputy martial law administrators along with Zia, it was Zia who became the public face of a regime that would soon go into the task of dismantling Bangladesh as it had come about in December 1971.

Observe the steps to regression, indeed to the decline of the secular Bengali state. On Zia’s watch, the Collaborators Order of 1972 was repealed in December 1975. In February 1976, the right-wing journalist Khondokar Abdul Hamid, who was to play a prominent role in the Zia regime, for the first time publicly spelt out the regime’s intention to impose ‘Bangladeshi nationalism’ on the country in direct contravention of Bengali nationalism. Hamid floated the idea at the Ekushey February programme organised by the Bangla Academy.

The country was on a slide, with the values associated with the War of Liberation coming under increasing assault by the dictatorship. The principles of socialism and secularism, two of the four fundamental pillars of the state, were prised out of the constitution by dictatorial fiat.

In early 1976, in a clear blow to the secular underpinnings of the state, a seerat conference, presided over by air force chief M.G. Tawab, who had been parachuted in from retirement in Germany days after the 15 August coup, opened at Suhrawardy Udyan. Every indication of the country being pushed into a direction at variance with its ideology was there.

It is against such a background of political regression resting on illegitimacy that the 30 May 1977 referendum needs to be analysed. Following on the murder and mayhem of November 1975, the referendum was but Zia’s second move to consolidate his hold on the state. Along the way he had had Colonel Abu Taher, who had engineered his rise to power through liquidating Khaled Musharraf, court-martialled and put to death in July 1976.

An Era of Unbridled Authoritarianism

And all the while his regime had busied itself in the odious job of pushing Bangladesh’s history under the rug and through that process airbrushing Bangabandhu, the Mujibnagar administration, indeed the principles associated with the War of Liberation out of the picture.

The 30 May referendum was a carefully crafted measure to strengthen Zia’s hold on politics. Nothing of even the remotely democratic characterised the move. The hope that under President Sayem, who had been installed in office by General Khaled Musharraf a mere day before darkness descended on the nation on 7 November 1975, the country could slowly but surely make its way back to democracy was belied.

In effect, the yes-no vote and a conscious pushing aside of genuine public perceptions about the regime were the very first step toward the imposition of an era of unbridled authoritarianism in the country. Worse, General Zia would preside over, after May 1977, a process of rehabilitation of the political collaborators of the 1971 Pakistan occupation army and have them make their cheerful way into the political landscape of a country they had virulently and violently opposed in 1971.

If in 1971 the people of Bangladesh were engaged in a life and death struggle against the Pakistan occupation army, in the Zia years it was a ceaseless struggle for them to prevent the regime from undermining the state through its dictatorial measures. Zia would, after May 1977, seek newer means of strengthening his grip on the country.

Ziaur Rahman's Presidential Election in June 1978

And that process would be a presidential election in June 1978, when the state machinery would assist Zia and the junta in helping to defeat General M.A.G. Osmany, the opposition candidate, at the ballot box. And then would come the formation of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, based on a brand of politics that was a wholesale repudiation of the spirit of 1971.

Zia’s objectives were revealed page by page as time went by. He had parliament, elected in February 1979 and in which his BNP held the majority, rubber stamp the notorious Indemnity Ordinance, aimed at giving immunity from prosecution to the assassins of the Father of the Nation and so have the rule of law subverted, into the fifth amendment to the constitution.

Nowhere in the world had a law been enacted and made part of the constitution to provide protection to assassins, but here was the Zia regime doing precisely that. Worse, a good number of Bangabandhu’s assassins were sent off abroad to serve as diplomats at various Bangladesh missions abroad.

In the Zia years, Bangladesh made its way back to Pakistan-era politics minus the Pakistan state. Through a systematic process of historical distortion, through paving the way for the country to pass under long-term and dictatorial rule by the military, General Zia ensured a retreat of democratic forces.

Additionally, his regime carefully prepared the ground for a sidelining of freedom fighter officers in the armed forces and the rise of officers repatriated from Pakistan after the war. Again, in a style reminiscent of the Ayub Khan era in Pakistan, the Zia regime sponsored the emergence of a civil-military bureaucratic structure in state administration, to the detriment of national politics.

Making Politics Difficult for the Politicians

Bangladesh, as history has demonstrated all too well, existed in shaky form in the Zia years. General Zia once arrogantly exclaimed that he would make politics difficult for politicians. He did something more grievous: he struck down the ideals associated with democratic politics.

Promise of power and pelf was a weapon the regime liberally employed in luring leftist as well as right-wing politicians into the BNP. The rise of the political turncoat became an embarrassing national reality in the Zia years.

On 30 May 1977, General Ziaur Rahman rounded out his ambition, in questionable manner, of commandeering the state of Bangladesh through imposing himself on the country.

Four years to the day, on 30 May 1981, his life came to a violent end in a putsch in Chittagong. In between, much blood had flowed, many lives had come to a sudden end, state principles had been turned on their head and democratic politics had become fugitive.

That referendum initiated an egregious trend . The corruption of politics, the process of voting being made a mockery of, the undermining of fundamental rights and the flouting of the rule of law — all of this was set in motion on that day in May forty-six years ago.

About the Author

Syed Badrul Ahsan is the Chief Editorial Adviser of The Confluence; a journalist and author. He previously served as the Press Minister at the High Commission of Bangladesh, London and authored a biography on the Founder of Bangladesh, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman entitled From Rebel to Founding Father: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

1 comment

Nicely Explained. The word has been chosen very consciously.