Countrywide general strikes, or hartals in our local parlance, were a necessary component of politics in the 1960s and all the way to the mid-1990s. There were the perfectly justifiable reasons for such expressions of public discontent with the state of politics in the country.

In the 1960s, hartals were a powerful means of drawing attention to popular anger at the mismanagement of politics, indeed undemocratic behaviour of a government foisted on the country (at that point the state of Pakistan, of which today’s Bangladesh formed the province of East Pakistan) by the army. The political opposition, of which the Awami League was a major component, utilised hartals as an effective weapon to not only to expose the authoritarian nature of the Ayub Khan regime but also to systematically weaken it in various ways.

The hartal of 7 June 1966 remains a pivotal chapter in the history of democratic awakening in Bangladesh. There was a simple reason. The strike, called all over East Pakistan, was a broad hint of the public support that was being expressed for the Six-Point plan of regional autonomy that had months earlier been announced by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in Lahore. That hartals were a legitimate weapon against dictatorship, that they were a barometer of gauging popular feelings on issues was manifested on 7 June all over the province.

In conditions of an absence of democratic and accountable government, hartals are the means through which people in our part of the world have consistently expressed their desire for political change. In March 1971, once it became clear that the Yahya Khan military junta, in cahoots with Z.A. Bhutto and his Pakistan People’s Party, was determined not to hand over power to an electorally triumphant Awami League, it was back to hartals as the weapon of resistance the Bengali nation went back to.

In the twenty-five days from 1 March to 25 March 1971, it was the writ of Bangabandhu which ran all over Bangladesh. With his party regularly issuing directives on the way Bangladesh, by that point a de facto sovereign state, would be administered, hartals continued to be a powerful message to the ruling classes of Rawalpindi/Islamabad that nothing short of a proper political solution to the crisis would be acceptable to Bengalis. It was a time when an entire nation of seventy-five million people weaponised hartals as the means of change.

In independent Bangladesh, with the people’s triumph in the War of Liberation, it was expected that hartals would become a thing of the past, would recede into history. Unfortunately, the carnage of 15 August, 3 November and 7 November of the year and their ramifications once again raised the prospect of a new agitation for a restoration of democratic governance in the country. The 1980s were a period when the nation’s political parties, grouped separately as the fifteen-party alliance led by the Awami League and the seven-party combine headed by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, engaged in relentless agitation against the Ershad military regime.

It was a necessary and inevitable struggle, given that the Ershad regime, in a manner similar to the Moshtaq outfit and the Zia regime earlier, was a brazen violation of the democratic process. The series of hartals, ceaselessly employed against the regime, was powerful evidence of the nation’s unwillingness to accept illegitimacy as part of the national political process. Those were productive hartals in the sense that they eventually forced the Ershad outfit from power in the way hartals in the late 1960s had compelled the Ayub Khan regime to bite the dust. Hartals opened the way to a restoration of democratic government through the general election of February 1991.

One would have thought there would be little need for hartals to come back after 1991, but they did when a rigged by-election in Magura in 1994 informed the nation that all was not well with democracy, that the future for political pluralism did not look bright. Between 1994 and 1996, the hartals called by the opposition Awami League and its allies to demand that a caretaker government supervise a fresh general election once again underscored the efficacy of such a mode of agitation in effecting political change. Hartals once more led to the departure of a government, an elected one, which had obviously failed to uphold constitutional politics in the country. The result was 12 June 1996.

Which brings one to the political agitation indulged in by the opposition today. The hartals and blockades which have been and are being enforced against the government in office militate against democratic politics for the good reason that the nation does not have a dictatorial regime in power nor is there any reason to suppose that the country is badly off in the economic sense of the meaning. Hartals in these times are being reduced to a state where they are being used to undermine a state which is home to an elected government that has presided over a remarkable degree of economic growth.

Hartals are a powerful weapon against authoritarian government. They are a means to pressure those in power to act in accordance with the provisions of the constitution. The irony today is that there is a constitutional government in place, that it is a government which was not imposed on the country and yet its opponents are adamant about overthrowing it before they can or will take part in the elections in January next year.

Of course, one will not suggest that this government has not made mistakes, does not suffer from flaws. But to argue that the government must simply hand over power to an interim administration in order for the opposition to participate in the elections is a faulty attitude to politics. And to enforce hartals and blockades toward achieving that goal ignores the point that such agitation is a weak and unnecessary means of bringing about political change, especially when the constitution is in force and parliament has functioned without interruption for the past so many years.

For the opposition, there are the many ways in which it can carry its message across to the country — through discussions, through meetings with the media, through public rallies, through seminars, through formulating policy and the like. Now that the election schedule has been announced and both the government and the Election Commission have promised to ensure a free, fair and uninterrupted process of voting, it should be for the opposition to abjure hartals and blockades (which have only been impeding the normal movement of citizens’ lives) and focus on its election strategy. Its economic programme, its foreign policy, its social uplift schemes, et cetera, are what citizens would be interested in knowing of.

Hartals were a necessary adjunct to politics at a time when the national objective was a restoration of democracy and constitutional government in the country. Today they are an anachronism, for they come in the way of the constitution, of elected government, of the lives and movement of citizens.

Politics is not about creating roadblocks to governance. It is about removing roadblocks and ensuring democratic continuity.

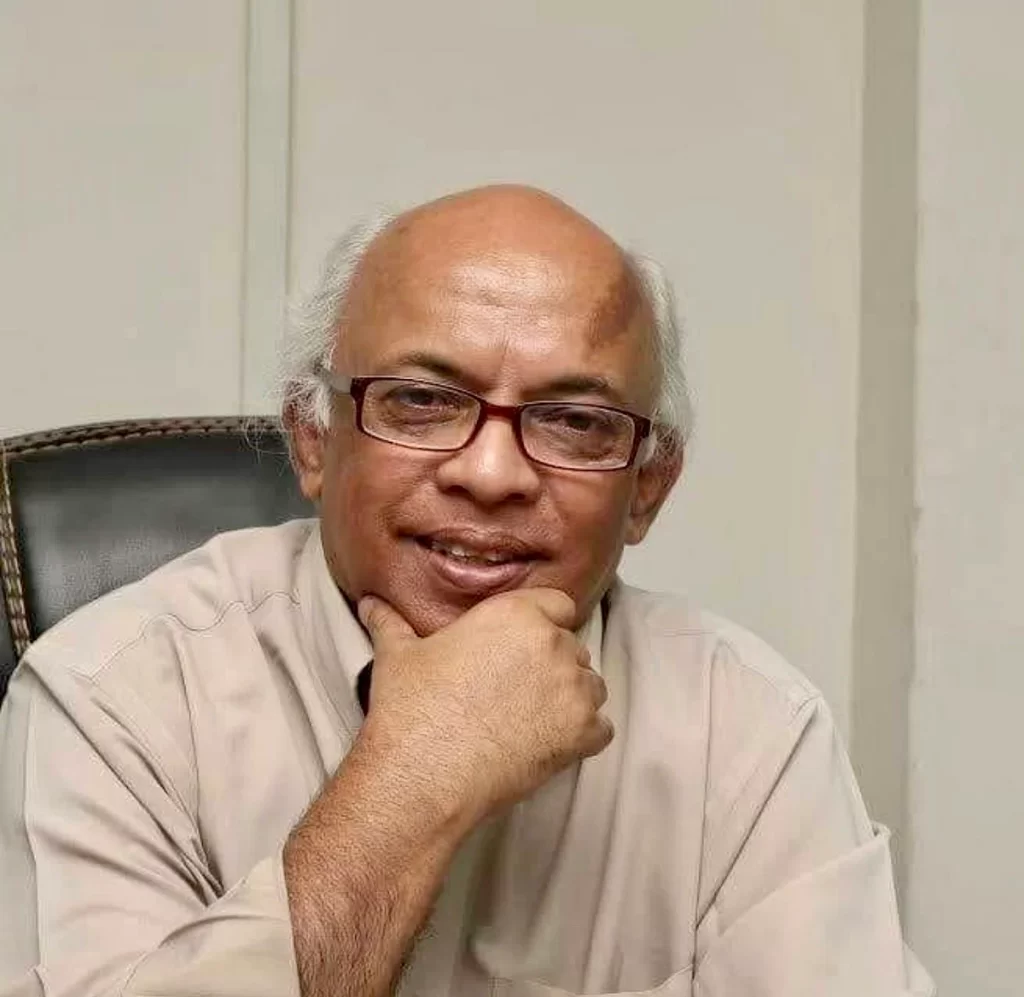

About the Author

Syed Badrul Ahsan is the Chief Editorial Adviser of The Confluence; a journalist and author. He previously served as the Press Minister at the High Commission of Bangladesh, London and authored a biography on the Founder of Bangladesh, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman entitled From Rebel to Founding Father: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

1 comment

Your title of the write-out is enough fair to middling to lamp shade about the message that is intended, expressed or signified!

In Julius Caesar, Shakespeare wrote in several famous anachronisms. When Caesar opens his shirt to the crowd, the play specifies that he is wearing a doublet. The greatest temptation for the like of us is: to renounce violence, to repent, to make peace with oneself. Most revolutionaries fell before this temptation, from Spartacus to Danton and Dostoevsky; they are the classical form of betrayal of the cause. If any political party’s chaos dominates their political world, then their politics is an anachronism; and every compromise withpeace-loving one’s own conscience is perfidy. When the maledict inner voice speaks to you, hold your hands over your ears…

You have veritably spelled out “Countrywide general strikes, or hartals in our local parlance, were a necessary component of politics in the 1960s and all the way to the mid-1990s. There were the perfectly justifiable reasons for such expressions of public discontent with the state of politics in the country.”

It is also truly true when you have written, “Hartals were a necessary adjunct to politics at a time when the national objective was a restoration of democracy…Today they are an anachronism, for they come in the way of the constitution, …and movement of citizens.”

Hartals, blockades, violence, arson, et al are antediluvian, an artifact that belongs to another time – now grossly offensive to decency or morality; causing horror to people and the country. “Politics is not about creating roadblocks to governance. It is about removing roadblocks and ensuring democratic continuity” are to the point!

The most powerful weapon you can be is an instrument of peace. The best weapon against an enemy is another enemy. The bat is not a toy, it’s a weapon. And Nelson Mandela’s beautiful words – that the most powerful weapon is not a gun or a bomb, but rather education – remind us that the world can change. In the long run, the sharpest weapon of all is a kind and gentle spirit.

But as a very long-time political observer since 1966, I also went to nearby Nayapaltan areas on 28th October, 2023 to see for myself what had been going there at BNP’s declared peaceful rally and I was there from about 10 am to about 4.30 pm. To my utter surprise, I watched Jamaat-e-BNP gangsters’ violent disorders and criminal offences all the while. These perps dissembled like anti-Bangladesh sub-humans as they belong to that political entity. Their temerity was found irremissible under any circumstances!!! These terrible goons must be dealt with iron-handedly.

— Anwar A. Khan, being a college student, was a direct witness of cruel birth of Bangladesh from a very close proximity in 1971 and a frontline FF of the 1971 war field