Did Sheikh Mujib perceive Bengali nationalism as a linguistic-nationalism, or as an ethno-nationalism, or as a territorial nationalism?

The ad-hominem tendency of fearing the name of nationalism in the neo-liberal academia has lost its path several times in the history. At the end of the first world war, industrial world applauded the idea of nationalism by welcoming the sovereignty of 26 new nations. However, stormed by the force of Nazism and Fascism, that position immediately reverted after the 2nd world war. Though, historically, the ‘age of exploration’ followed by the global race of European colonisers along with the very initiation of industrialisation was an ‘achievement’ of competing Nation-states, these industrialised Nation-states suddenly realised the dark side of Nationalism only after the 40s and so did their academia.

Yet, the magical liberating power of nationalism kept itself alive in the developing world while assisting Vietnam, Indonesia, Syria, India, Pakistan, Burma, Sri-Lanka, Bhutan and many more in their decolonisation process and honestly, nobody complained. Then again when the cold war hit the west, Nationalism presented itself in its juvenile form. ‘Fall of socialism’, though was credited to the victory of neo-liberal ideologies, was more of a victory for Nationalism allowing sovereignty to 19 new nation-states at the end of cold war.

Is Nationalism necessarily toxic?

On the one hand, theorists have often seen Nationalism as a revivalist tendency of political elites quoting the past glory; on the other hand Nationalism has also been seen as the instrument to politicize a sense of identity amongst the masses and creating ‘nation’ in the process. Both of these primordial and instrumental theories have their supporters and applications. However, the truth, perhaps lies in between the two. In fact, Nationalism is a political ideology that has a backward looking and a forward looking face, both at the same time. It takes inspiration from the past but does not necessarily promise to revive it, rather plans to ensure a safe journey towards modernity. Indeed, like any other political ideology, in the process Nationalism often carries out processes like alienation, otherisation, annexation and many things more. But in this postcolonial world, one thing Nationalism does not do is guising itself as a uniform, global ideology; one quality that Communism, neo-liberalism, Islamism all have in common. As a result, Irish nationalism functions differently than Scottish nationalism; Indian nationalism aspires different things than Arab nationalism, Chinese nationalism presents different possibilities than Bengali Nationalism, thus the idea of Internationalism can represent diversity.

This uniqueness of Nationalism spirals primarily from the geographical diversity or distinction amongst the world territories. Geography, thus may not be the prison for the nations as some claim, but certainly is the home for them. Distinctions such as linguistic-nationalism, ethno-nationalism, territorial nationalism, civic nationalism, economic nationalism etc emerged as a result. This article aims to discuss Bengali Nationalism in its historic and current form. More specifically, it delves into a search for the perception that Sheikh Mujib, the founding father of the only Bengali nation-state had held towards nationalism. Did Sheikh Mujib perceive Bengali nationalism as a linguistic-nationalism, or as an ethno-nationalism, or as a territorial nationalism?

History of 'Bengaliness"

The Bengali identity, gained political significance during the Bengal Sultanate, when this identity has been instrumentalised by the Bengal sultans to create a socio-cultural polity distinct from the neighbouring land of Hindustan. Promotion of this newfound territorial identity is clear from their official inscriptions and explorers’ accounts such as Abdul Hamid Lahori’s ‘Padshahnama’. However, the uniqueness of this Eastern-Indian territory which has ‘Bongo’ at its centre, has always been historically and prehistorically sustained by the geography. This unique piece of land emerged at the junction of Indian and Burmese tectonic plates due to the sedimentary plain laid by the Himalayan streams, which makes its nature distinct from any other place on earth. Hence, emergence of this identity was not just a political ploy, but a geopolitical necessity influenced by geography and obliged by the ruling empires perpetually. Though, the academic use of the term “Bengali Nationalism” initially surfaced in the early 1900 during the anti-partition movement of Bengal; nationalist politician and theorist C R Das rightly claimed that “… like gravity existed before Newton, our nation (Bengali) too existed before the English invaded. Our inability to realise it doesn’t make it non-existent.”

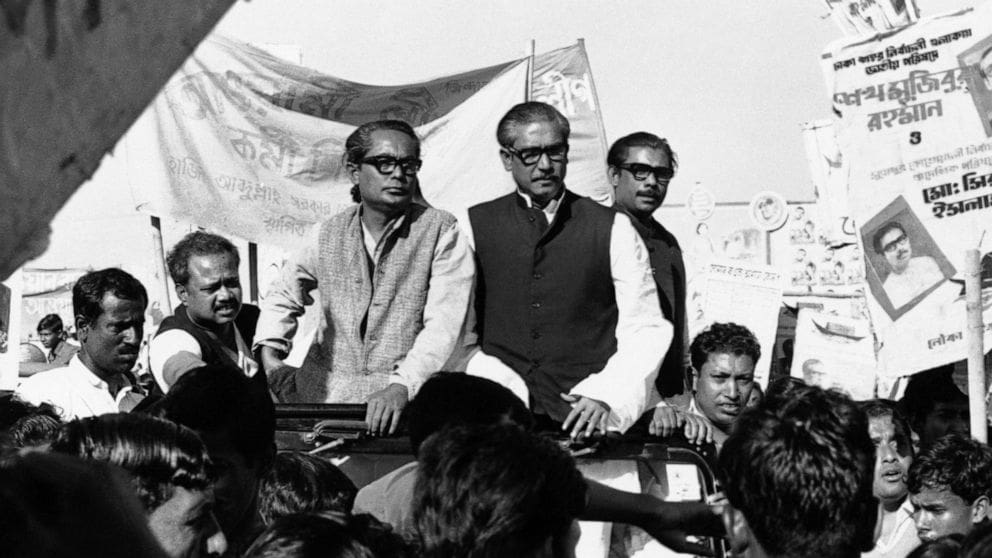

However, it is also true that initially due to the ongoing wave of decolonisation across the Indian continent; the idea of Bengali Nationalism was often mistakenly perceived as a sub-set of Pan-Indian nationalism. Efforts were also made to change this perception. Rabindranath’s Rakhi festival gained its footing in protest of the 1905 Bengal Partition which later influenced song like Amar Sonar Bangla. C R Das’s Bengal Pact created genuine hope but diminished with the sudden demise of the visionary. Then the penultimate and futile effort of Basu-Sohrawardi’s proposal of “Bengal Free State” just before the wave of Religious-nationalism took the Indian subcontinent by storm, giving birth to two new state machineries with transnational federal structures. But, from these debris of the Bengal neverland, emerged leaders like Sheikh Mujib who started planning for a national future keeping the past successes and failures in mind. Although, for the sake of political correctness, Mujib’s perception of Bengali Nationalism is popularly described as an ethno-linguistic nationalism, the progression of events in his political career rather directs towards a more territorial turned civic nature of his nationalist politics.

Mujib's Nationalism

These nationalist efforts by Sheikh Mujib were first alleged in the new-born state of Pakistan by their police intelligence, and later confirmed in the new-born state of Bangladesh by the head of the government himself. In this interview with Annodashankar Roy on the afternoon of 24th April 1974, Sheikh Mujib quite frankly confirmed his commitment to the idea of Bengal Free State proposed by the Basu-Wardi duo and also the strategic reversion from the direct activism towards it, being the real politician he was. Interestingly enough, this later move was also reported by the Pakistani detectives in the late 40s. Though, he suspended the explicit activism of territorial nationalism, it is clear from the later turn of events that his implicit efforts were never seized. In 1954, in the travel log on his China visit of 1952, he specifically stated his perception of “Bangladesh” being shared by India and Pakistan. This is the first ever written evidence of the word “Bangladesh” appearing in his own account. Later, in 1956, during a Dhaka University event attended by the West-Pakistani members of Constituent Assembly, Sheikh Mujib explicitly requested to play “Amar Sonar Bangla”, the song that has a specific suggestiveness towards the territorial integrity of Bengal both historically and musically, on the stage.

Insinuation of Mujib’s territorial nationalism again surfaced when the official name of East-Bengal was decided to be changed by the Pakistani ruling class. The emerging nationalist leader, in 1957, stormed the constituent assembly with protest and reiterated the significance of the name ‘Bengal’. He did not shy away from uttering the historic importance of the name and later in 1969 declared the state as “Bangladesh” (The land of Bengal). One may turn a blind eye in self-ignorance, but choosing the death anniversary of ‘THE’ H S Sohrawardy of Basu-Sohrawardy proposal, to rename a territorial entity was nothing short of a political masterstroke played by a legendary nationalist leader. The symbolism is hard to ignore even for a political novice.

Like any other adept real politician, Sheikh Mujib too maintained ambiguity instead of prematurely talking about potential ideas which can be explosive. Even in the constituent assembly of Bangladesh, he indistinctly defined the idea of being Bengali as the “feeling of being Bengali”, avoiding the popular ethno-linguistic definitions. Yet, he vocally supported the first basic principle of the 1972’s Bangladesh constitution- “Bengali Nationalism”. While talking to Syed Muztaba Ali and Santosh Ghose, he differentiated the “Political Union” of India from the “Cultural Nation” of Bangladesh, equating India with the continent of Europe. Yet, the wartime flag of Bangladesh was stripped off of the geographical demarcation it had within two days of his return to the newly born republic.

Mujib expressed his sturdy inclination in importing only Bengali films from the Indian union, and being slighted he barred import of all foreign films except English. He affirmed Ved Marwa, the young Indian diplomat with a mission to comprehend the growing headache for the Indian Union called “Bengali Identity”, mid-air, by his personal identity of being Bengali, Human and Muslim. Yet, he adopted the “citizenship” identity of the people of Bangladesh as “Bangalee” in a very civic fashion which is common in European nation-states like Germany, Netherlands, Ireland etc. He equated the nationalist chant of “Joy Bangla” directly with secularism when requesting Mujahidul Islam Selim to utter the slogan. To Sheikh Mujib, secularism came more as a pluralist necessity to accommodate the inherent religious diversity of the Bengali nation. It makes more political sense for a territory where multiple major religious communities coexist, than for a republic with overwhelming majority of one particular religion.

Bangladeshi Vs Bengali/Bangalee

Hence, no matter however diplomatically concealed his intentions were kept, the inclusion of “Bangalee” citizenship along with adopting Bengali Nationalism as the leading basic principle of Bangladesh, did create discomfort in the intelligentsia of the Indian union. Personalities like Basanto Chaterjee, Santosh Ghose and Kuldip Nayar argued for a different identity for the citizens of Bangladesh, and the term “Bangladeshi” was coined as a revised territorial civic identity with an apparent secular outlook. This, however, became the major anti-thesis against the vision of “Bengali Nationalism” in the post-Mujib era of Bangladesh. As Anthony Mascarenhas puts it-

The poster argument, however, for the “Bangladeshi Nationalism” is to claim that “Bengali” is an “ethnic identity”, thus not accommodating of any other ethnicities present in the republic. Quoting a loosely referenced statement addressing the Chakma Leader M N Larma following the constituent assembly debate- “… Tora Bangalee hoiya ja (you too become Bangalee)”, Sheikh Mujib is misinterpreted as an ethno-nationalist totalitarian. However, the discussions above argued why that was wrong.

Neither Sheikh Mujib perceived Bengali as an ethnic identity, nor did he perceive Bengali Nationalism as an ethno-nationalism. Rather, like Frisians of Germany and Netherlands are accommodated within the territorial turned civic identity of German and Dutch “citizenship” respectively, he proposed the same for the inhabitants of the newfound nation-state of Bengal. It will be whimsical to demand renaming of the German, or Dutch, or Irish citizenship identity into Germanic/Netherlandic/Southern-Irelandic one fine morning.

Considering Sheikh Mujib as the principle proponent of the modern Bengali nationalism, claiming for a revisionist, downsized and pseudo-secular “Bangladeshi” identity is equally nonsensical. Though, sense barely prevails in this ridiculous world, one can always hope; for “Hope” as per Vaclav Havel, the legendary Czech nationalist “…is not the conviction that something will turn out well but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out.”

About the Author

5 comments

Joy bangla

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

[…] the movement to cleanse the country of such impediments to the rule of law and to the concept of Bengali nationalism as ingrained in the history of Bengali cultural and political history over the decades. The young […]

[…] at that early stage was to shape a strategy that would be a clean break with the concept of Bengali nationalism as it had come to be articulated since the mid-1960s when Bangabandhu and the Awami League had […]

[…] and five years have shaped the history of the Awami League and by extension forged the history of Bengali nationalism, enough to steer Bangladesh to sovereign statehood. The story of the Awami League has been a […]