It was that hallowed moment when history was forged through blood and sweat and tears. It was a time when Bengalis, traditionally in love with poetry and song and mysticism, decided in the emergent extremity of circumstances to take up arms in defence of national dignity. It was that moment when the Bengali nation went out into the world, to inform men and women everywhere that freedom was its goal, that it had turned its back on the past as it strove to construct a future resplendent in the beauty of liberty.

The emergence of the provisional Bangladesh government in Mujibnagar, fifty two years ago on this day on 17 April 1971, was a defining moment for the Bengali nation. The first Bengali government in history, administered by Bengalis and for Bengalis, it took shape in the grey region between the sinister and the illuminating. The sinister was the programmed genocide launched with unprecedented viciousness by the Pakistan occupation army; and the illuminating was the truth that such a brutal assault on human dignity, indeed on the traditions of a people, could not go unchallenged and unbeaten.

And so it was on 17 April 1971 that in Meherpur of Chuadanga, the senior leaders of the Awami League, close associates of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, came together to proclaim before the world that out of the debris of a fast enveloping war and the smoke of a disappearing East Pakistan had emerged a government, the overriding purpose behind the act being the liberation of the Bengali nation.

That making of history followed the Proclamation of Independence earlier drafted on 10 April. It followed a strategic linking up between the Indian government and the Bangladesh political leadership through Tajuddin Ahmad, a trusted lieutenant of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, meeting Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in Delhi

Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmad, M.Mansoor Ali and A.H.M Kamruzzaman, along with the extended leadership of the Awami League, informed their fellow Bengalis and then the world that occupied Bangladesh was ready for a guerrilla struggle against Pakistan. It did not matter that Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had been spirited away in prison somewhere in Pakistan. But it did matter that he was the symbol of the struggle about to be unleashed by a nation brutalized by savagery. He was the Father of the Nation.

Long hours had been spent working out the details of the announcement of the government, its line-up and its objectives. Amir-Ul Islam, the eminent lawyer, had worked on the Proclamation of Independence that would be read out on the occasion. And Yusuf Ali, teacher turned politician, was there to do the job. He would do it with finesse. Journalists from the global media had been told of the event and on the day would make sure they were there to take in the measure of Bengali resistance to Pakistan.

The moment was a first for Bengalis in their thousand-year history. Of course, Sirajuddoulah, the last independent nawab of Bengal, had perished in 1757, waging war against the British and their local cohorts in defence of a lost cause. But here was Bengal, or the eastern part of a whole truncated already through the tragedy of partition in 1947, ready to rise in defence of its self-esteem.

There was a qualitative difference between Sirajuddoulah and the men about to transform themselves into a government in April 1971. It was simple: the political structure which Tajuddin Ahmad and his associates hurriedly cobbled into shape would be the first Bengali national government in history. Never before had Bengalis governed themselves. Now, caught between a rock and a hard place, the government that would come to be known as Mujibnagar had chosen to strike back in order to take centre stage in the historical scheme of things.

Much good and many unprecedented events flowed from 17 April 1971. The essence of it all was the creation of a sense of purpose among the Bengali nation. Students, academics, doctors, lawyers, artistes, politicians, civil servants, journalists, diplomats, soldiers, writers, poets, policemen — all rallied to the cause — because the Mujibnagar government was there as the voice of the nation. Thousands of young men simply marched from their villages and their small towns and then trekked through woodlands and swam across streams and rivers to link up with Mujibnagar.

What had till 25 March been the improbable turned out to be the eminently possible. Songs of revolution that Bengalis had never heard before became part of their existence through Shwadhin Bangla Betar. Bengali officers of the Pakistan army, now no more with it and very much a moving force behind the resistance, forged a guerrilla force named the Mukti Bahini and let it loose upon the marauding men from the mountains of the distant west. The land needed to be reclaimed from the genocide makers.

What if the Mujibnagar government had not taken shape? What if the men who would lead the armed struggle against Pakistan had chosen to spend the rest of their lives waiting for a negotiated settlement to the crisis? What if, in the absence of resistance, Pakistan had perpetuated its presence in Bangladesh and cast its ever-darkening shadow on Bengali heritage?

Prior to 17 April 1971, these fears were all too real for the nation to dismiss out of hand. Bangabandhu had been abducted by the Pakistan army; and not one of us knew where the rest of the Awami League leadership was at that point. We would, of course, know subsequently that even as we worried about the future, Tajuddin Ahmad and Amir-Ul Islam were making frantic efforts to locate the other men who would form the core of the Mujibnagar government.

Over a period of nearly a month, even as the genocide by the Pakistan occupation army went on, Syed Nazrul Islam, Mansoor Ali, Kamruzzaman, M.A.G. Osmany and a host of others would come together to translate the idea of freedom into the reality of sovereignty.

It is that lighting of the candle in the dark we celebrate this morning. The men who built the edifice of Bengali resistance little knew before 25 March 1971 of the huge impediments that lay ahead of them. They were men whose belief in constitutional politics had been total and unequivocal.

And yet these were the men on whose shoulders devolved the responsibility of guiding a bewildered, frightened nation to freedom through an armed struggle. They did the job exceedingly well. They shaped a revolution that would put into global political orbit the first sovereign Bengali republic in history.

In April 1971, we shaped the course to the future. Much blood would flow between the arrival of the Mujibnagar government and the rise of a liberated Bangladesh. Three million Bengalis, murdered by the soldiers, would not be witness to the sunlight of freedom. Tens of thousands of Bengali women would be prey to the rapacity of the occupation army. Villages would be pillaged, towns would be set to the torch. Bangabandhu would be put on a sham of a trial a thousand miles away.

In all that gloom, Mujibnagar was our lamp in the dark. It would light our way out of the dense, dark woods into an expanse of freedom. ***

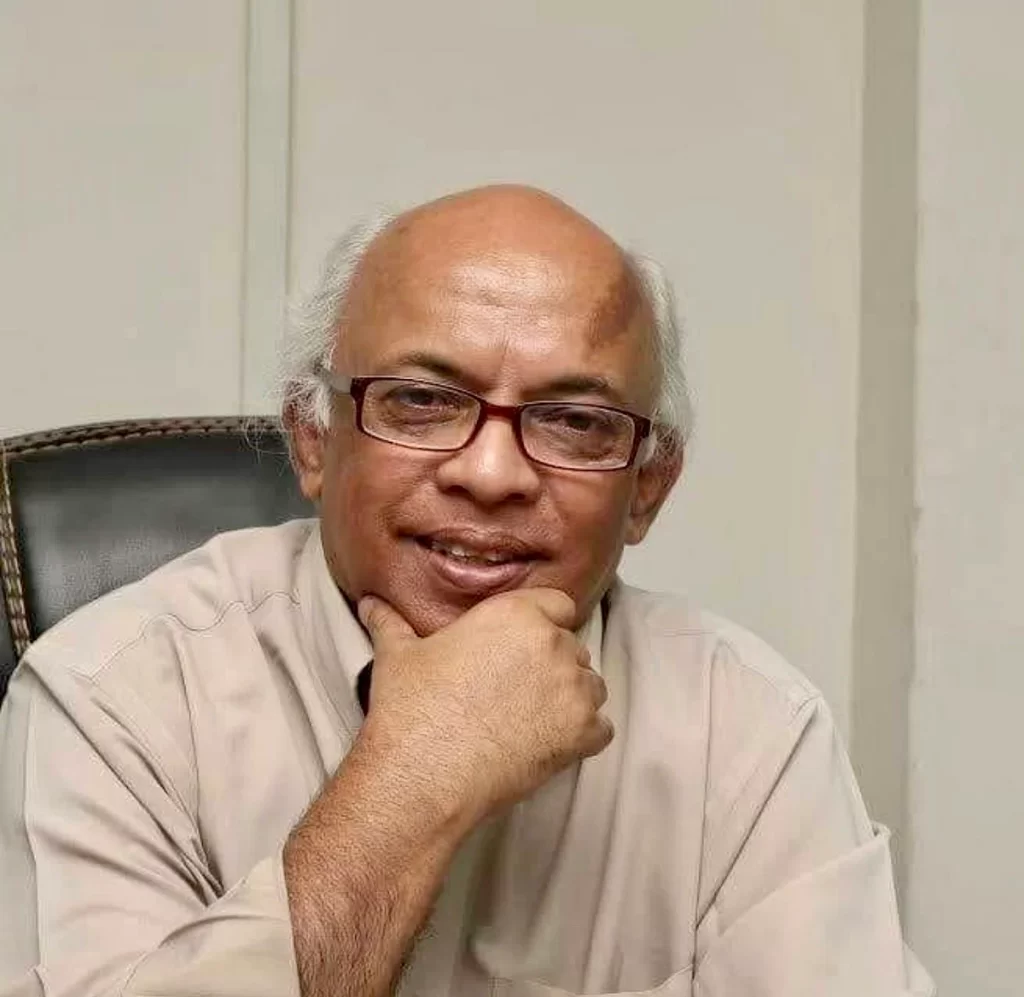

About the Author

Syed Badrul Ahsan is the Chief Editorial Adviser of The Confluence; a journalist and author. He previously served as the Press Minister at the High Commission of Bangladesh, London and authored a biography on the Founder of Bangladesh, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman entitled From Rebel to Founding Father: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.