Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana, the two daughters of the Father of the Nation, through sheer luck, escaped the tragic events of 15th August 1975. But what happened thereafter?

When Sheikh Hasina came home following six years of life in exile abroad, it was a changed world she was making her way to.

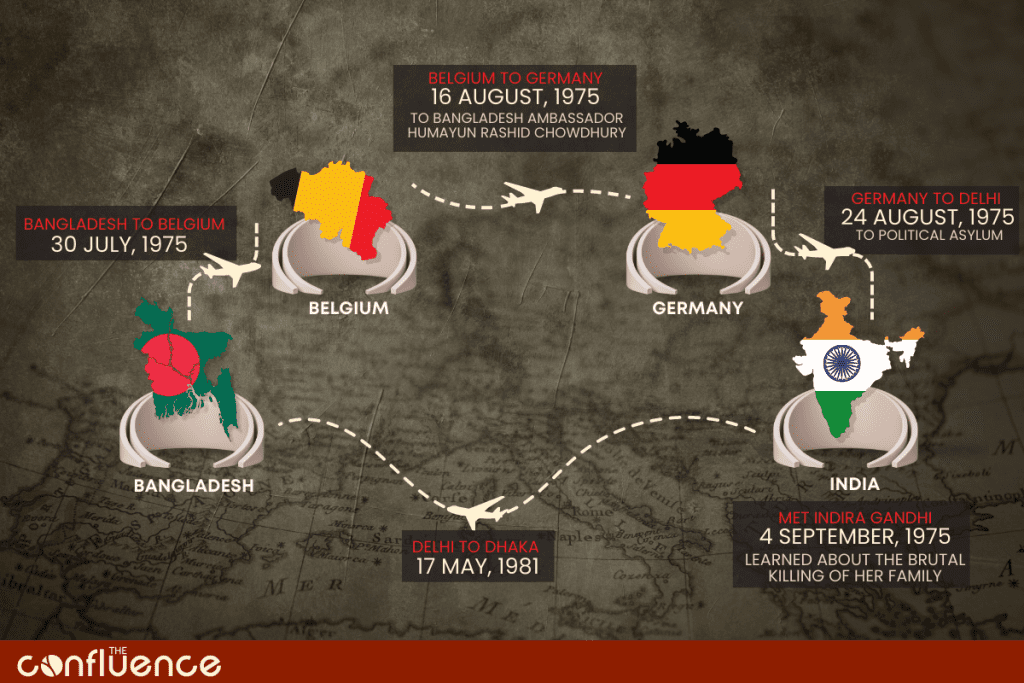

The world had changed, her world. Having travelled to Europe with her husband and younger sister Rehana, at the end of July 1975, largely on a tourism-related trip, she was compelled to stay away from the country for close to six years. When she left home in the summer of 1975, it was a vibrant, thriving family she left behind. Bangabandhu missed her absence and that of her sister and wanted them to return home.

And then the world changed for Sheikh Hasina, indeed for the people of Bangladesh. The assassinations of August 1975 precluded her homecoming. An entire family had been gunned down in one of the most shameful of moments in time. The assassins and the usurpers who seized the state made sure that Sheikh Hasina did not and could not come home.

Homecoming

In May 1981, Sheikh Hasina, newly anointed as chief of the Awami League by the associates and lieutenants of her father, did come back home. The military regime of General Ziaur Rahman and its political collaborators, having spent five years in denigrating Bangabandhu and the War of Liberation, were powerless to put up roadblocks before the leader of a party which clearly now had a future before it, for itself and for the nation.

It was a rain-enveloped afternoon when Sheikh Hasina came home. But she would not yet have the opportunity to visit her Dhanmondi home, home that stood witness to the glorious moments of Bangladesh’s history, for it was yet under the occupation of the forces of political illegitimacy.

But circumstances would soon change and 32 Dhanmondi, ransacked and bullet-ridden, would again be open to her and to the Bengali nation. The lights would go on again; and Bangabandhu’s daughter would inform the nation that she had arrived, literally as well as metaphorically, to steer the boat to newer shores.

Situation of the World

Around the world, much political change had taken place. Indira Gandhi, losing power in 1977, had ridden back to office in triumph in 1980. Away in the United States, Ronald Reagan was in his fourth month in office as President. In Britain, Margaret Thatcher was at 10 Downing Street. In the month when Sheikh Hasina came home, Francois Mitterrand had finally made it to the Elysee as France’s new President. The Chinese, with Deng Xiaoping in charge, were creating new political and economic opportunities for themselves in the absence of Mao Zedong and Zhou En-lai.

Pakistan, no stranger to military rule, groaned under the weight of the Ziaul Haq regime, which two years earlier had sent Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to the gallows. An ailing Leonid Brezhnev shakily presided over the Soviet Union less than two years after sending his forces into Afghanistan. In Iran, the Ayatollahs ruled following the fall of the Shah in 1979.

Such was the world Sheikh Hasina came home to on 17 May 1981. And from there on she would move on to change our world here in Bangladesh. General Ziaur Rahman was yet in charge, though a few weeks later he would be murdered in a military putsch in Chittagong.

Sheikh Hasina Reinstating Awami Politics

For Hasina, her homecoming would lead to a new democratic opening and she would take her followers down that road to justice, to the rule of law, to a restoration of secular pluralism. Her nation invested heavily in her, for her people saw her as the embodiment of the restoration of the politics and the historical process that had been interrupted in August-November 1975.

The Awami League under Sheikh Hasina would come together again on a single platform, with all its factions, as one united organisation, reviving the old dreams of providing positive leadership to the country. The party would wage a spirited struggle against a new usurper regime, that of General Hussein Muhammad Ershad.

In the process it would pay a price for its adherence to principles. It would go for elections called by the regime in 1986, in the expectation that it would be able, together with the political combine led by Khaleda Zia, to drum out the general and his acolytes through an electoral rejection of their outfit.

That did not happen; and the BNP swiftly went into a condemnation of the Awami League, terming its participation in the election as a betrayal. For its part, the Awami League would have the nation know that it and the BNP had had a seat-sharing deal aimed at showing the regime the door, but that the BNP had at the last moment reneged on it.

A New Frontier for Awami League

For the next two years, Sheikh Hasina and her party remained focused on two factors: keeping up the pressure on the regime in order for it to go and for the Awami League to go back to the people in a new movement for support. That moment came for Sheikh Hasina in 1988, when the Jatiya Sangsad lost credibility and had the regime lose face.

The Awami League, now out of parliament, went on to sketch the outlines of a broader struggle for democracy. The struggle reached a happy culmination with the removal of the Ershad regime through a mass upsurge in December 1990.

The Awami League, expected to ride back to power at the February 1991 general elections, ended up losing the vote. Taking its place as the opposition in parliament, the party under Sheikh Hasina kept the new government on its toes, all the while planning for a return to office.

The rigged by-election in Magura in 1994 gave the party the perfect opportunity to demand fresh general elections under a new caretaker administration. It was not to be an easy ride for Sheikh Hasina, but the struggle for change registered increasing levels of intensity as the weeks and months wore on. In early 1996, change began to assume the shape of possibility.

On 12 June 1996, after years of repression exercised against leaders and workers of the party, after more than two decades of harassment and subjection to innuendo and calumny, Sheikh Hasina led the Awami League back to power twenty-one years after the government led by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had been overthrown in murder-drenched conspiracy.

Awami League in Government

It was the beginning of a new era for Bangladesh’s people. Steps were taken to have the notorious indemnity ordinance, designed to protect the assassins of the Father of the Nation and incorporated in the constitution by the Zia regime through the fifth amendment, repealed by parliament.

A good number of the killers were rounded up (the others having stayed on as fugitives abroad) and placed on trial. A deal on a sharing of the waters of the Ganges was reached with India; and an agreement on ending the insurgency in the Chittagong Hill Tracts was reached with the Chakma rebels.

In June 1996, there were all the hints of a rolling back of the darkness that had loomed large over Bangladesh. Light was spotted at the end of the long sinister tunnel. The meaning of liberty was renewed and hope of a revival of democracy based on secular politics burned bright.

In 1996, Afghanistan was beginning to splinter into fragments; Deng Xiaoping was yet in office as China’s paramount leader; the Soviet Union had become history; HD Deve Gowda held office as India’s Prime Minister; Bill Clinton was preparing for a second term in the White House; and Tony Blair and Gordon Brown would within a year take the Labour Party back to power in Britain. Benazir Bhutto was in her second stint as Pakistan’s Prime Minister.

In June 1996, Bangladesh looked to a new dawn – of a restoration of the values which had underscored its emergence as a sovereign People’s Republic in 1971.

About the Author

Syed Badrul Ahsan is the Chief Editorial Adviser of The Confluence; a journalist and author. He previously served as the Press Minister at the High Commission of Bangladesh, London and authored a biography on the Founder of Bangladesh, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman entitled From Rebel to Founding Father: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.